Text is not dialogue

Text is not enough - humans learn through imitation, interaction and community

In education writ large, we've become overly dependent on text-based instruction and assessment. Worksheets, textbooks, and written assignments dominate classroom practice, creating learning environments that prioritize the written word over other forms of communication and cognition. As Merlin Donald's (2006) research on cognitive evolution reveals, human cognition developed through distinct stages—Mimetic, Mythic, and Theoretic—with text-based learning representing only the most recent layer. Our excessive focus on text neglects the deeper, more fundamental cognitive systems through which humans naturally learn.

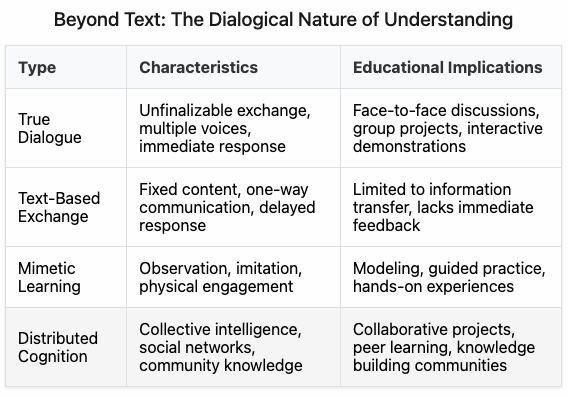

Dmitri Nikulin's analysis of dialogue, building on Bakhtin's theories, further illuminates this problem by distinguishing between true dialogue and mere information exchange. According to Nikulin (2006), authentic dialogue involves the unfinalizable exchange between independent voices, each expressing their unique "eidema" or personal essence. Contemporary classrooms often engage students in text-based "non-dialogical conversation" that "simply conveys information" (Nikulin, 2006, p. 156) rather than fostering genuine dialogical exchange that involves the whole person and acknowledges the incomplete, evolving nature of understanding.

By recognizing that text is not dialogue, educational leaders can begin to reimagine classroom communication in ways that honor our evolutionary cognitive heritage. This requires moving beyond the limitations of text-based instruction to embrace the mimetic foundations of learning and the dialogical nature of understanding. When we design learning environments that incorporate embodied knowledge, face-to-face interaction, and distributed cognition, we align educational practice with how humans naturally learn and develop. This post explores practical approaches to balancing textual learning with the mimetic and dialogical dimensions essential to deep understanding.

The mimetic foundation of learning

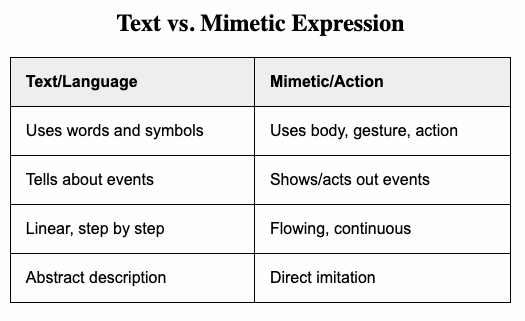

Text-based instruction often fails because it bypasses our most ancient and fundamental learning system. Donald (2006) identifies mimesis—our ability to learn through observation, imitation, and rehearsal of skills—as the earliest uniquely human cognitive adaptation, emerging approximately two million years ago. Unlike simple mimicry, mimesis involves understanding purpose and intention while allowing for creative refinement of actions. This capacity provided the evolutionary platform upon which language and symbolic systems later developed. Yet in contemporary classrooms, we often privilege written instruction over demonstration, physical engagement, and practice, creating a mismatch between our teaching methods and students' innate learning capacities.

The limitations of text become apparent when teaching complex skills that involve intricate sequences of movements or procedures. Donald explains that mimesis is "amodal" and integrates multiple sensory channels, allowing humans to map perceived events onto action patterns using their entire bodies. This explains why skills like playing an instrument, conducting a science experiment, or mastering a craft cannot be adequately conveyed through text alone. A student reading about how to throw a pot on a pottery wheel gains little compared to one who watches an expert potter, receives guided practice, and engages in deliberate rehearsal. The text-dominant classroom deprives students of learning through this evolutionary-established pathway.

Our reliance on text also undermines the social foundation of mimetic learning. Donald (2006) argues that mimesis enabled the first human cultures by facilitating the sharing of skills and establishing communal practices. When classroom communication becomes predominantly text-based, students lose opportunities to observe and emulate not just academic skills but also social behaviors, problem-solving approaches, and emotional regulation strategies. The master teacher who models thinking processes aloud, demonstrates emotional resilience when facing challenges, and exhibits curiosity and wonder provides mimetic lessons that no textbook can convey. Educational approaches that balance text with rich mimetic experiences leverage our evolutionary inheritance and activate more complete learning pathways.

The dialogical nature of understanding

Text-based communication frequently fails to achieve the essential qualities of true dialogue. According to Nikulin (2006, 2010), genuine dialogue requires the presence of independent yet interconnected voices, each expressing their unique perspective while remaining open to transformation through interaction. In his analysis of Bakhtin's work, Nikulin (1998) emphasizes that dialogue is fundamentally "unfinalizable"—it resists closure and finality, remaining always open to new meanings and interpretations. Text-based classroom communication, by contrast, often presents knowledge as finalized and authoritative, leaving little room for the "dissensus" that Nikulin identifies as essential to dialogue's vitality.

The asynchronous nature of most textual communication creates additional barriers to dialogue. When students read textbooks or complete written assignments, they engage with fixed content that cannot respond to their questions, confusions, or insights. Even when digital technologies enable some interactivity, these exchanges typically lack the immediacy and responsiveness of face-to-face dialogue. Nikulin (1998) argues that dialogue requires "simultaneity" where voices "sound everywhere" without "one focal point where the polyphony can be heard" (p. 385). This simultaneity—the ability to perceive multiple perspectives at once and respond in real-time—is diminished or lost in text-mediated exchange.

Authentic dialogue requires what Nikulin calls "benevolence" and equality among participants—conditions often absent in text-dominant classrooms. The authority vested in textbooks and written assessments frequently positions students as passive recipients rather than active contributors to knowledge construction. As Nikulin (2006) observes, dialogue demands that participants exercise "goodwill" and demonstrate a "readiness to listen to the other" (p. 252). Face-to-face communication, with its rich nonverbal dimensions, creates opportunities for establishing the trust and reciprocity essential to dialogical exchange. When teachers and students can see, hear, and respond to one another directly, they create conditions for genuine dialogue that text alone cannot sustain.

Distributed cognition and the classroom community

Text-based instruction often treats knowledge as something contained within individual minds rather than distributed across social networks. Donald (2006) describes human cultures as "massive distributed cognitive networks" that link many minds and extend individual capabilities through collective intelligence. Classrooms function as microcosms of these broader networks, with understanding emerging not just within individual students but across the community. Over-reliance on text tends to isolate learners, limiting their access to this distributed intelligence and reinforcing the myth of learning as a solely individual achievement.

The distributed nature of cognition becomes evident when we consider how knowledge actually develops in professional communities. Scientists don't work in isolation with texts; they collaborate in laboratories, debate at conferences, and build on each other's discoveries. Artists learn in studios through apprenticeship and critical feedback. Yet classroom learning often substitutes these authentic knowledge-building practices with decontextualized reading and writing tasks. Donald (2006) notes that "distributed cognition can exploit the specialized talents of individuals by combining them into a collective cognitive organ," but this potential remains largely untapped when classroom communication centers primarily on text.

While digital technologies have expanded possibilities for distributed cognition, they often perpetuate text-dominant approaches rather than transcending them. Online discussion boards, shared documents, and learning management systems can facilitate certain kinds of collaboration, but they typically privilege written communication over other forms of exchange. Donald (2006) describes how technology can "actually alter the properties of the distributed cognitive systems" and "change the nature of the cognitive work that is done." The challenge for educators is to design learning environments that leverage technology to support genuine distributed cognition—combining face-to-face interaction, hands-on collaboration, and thoughtful use of both digital and physical tools to create knowledge-building communities that transcend the limitations of text.

Implications for educational practice

Educational leaders must reimagine classroom communication by balancing text with other modes of learning and interaction. First, incorporate regular demonstration and modeling, where teachers and skilled peers make their thinking visible through direct demonstration. Structure frequent opportunities for guided practice with immediate feedback, allowing students to develop skills through mimetic learning. Second, design physical learning environments that facilitate face-to-face dialogue through flexible seating arrangements, collaborative spaces, and areas for demonstration and performance. The classroom should support multiple modes of communication beyond text, including oral discussion, visual representation, and embodied expression.

Reconsider assessment practices that privilege written products over other demonstrations of understanding. Performance-based assessments, project presentations, debates, and exhibitions allow students to demonstrate knowledge through multiple modalities. Documentation strategies can capture evidence of learning from dialogical exchanges and collaborative work—not just individual written products. Train teachers to recognize and value students' contributions across various communication channels, not merely their ability to produce polished text. This doesn't mean abandoning writing instruction; rather, it means situating writing within a richer communicative ecology that includes oral, visual, and embodied expression.

Develop professional learning communities that help teachers balance textual and non-textual approaches to instruction. Provide training in facilitating productive dialogue that moves beyond the typical Initiation-Response-Evaluation pattern to foster genuine exchange. Help teachers recognize when text-based instruction is appropriate and when other modes would better serve learning goals. Support them in designing hybrid learning environments that integrate digital tools with face-to-face interaction, leveraging the benefits of technology without surrendering to text-dominated communication. By acknowledging that text is not dialogue, we open possibilities for classroom communication that engages students' full cognitive capacities and prepares them for a world where success demands far more than textual literacy alone.

References

Donald, M. (2006). Art and cognitive evolution. In M. Turner (Ed.), The artful mind: Cognitive science and the riddle of human creativity (pp. 3-20). Oxford University Press.

Donald, M. (2006). Imitation and mimesis. In S. Hurley & N. Chater (Eds.), Perspectives on imitation: From neuroscience to social science (Vol. 2, pp. 283-300). MIT Press.

Nikulin, D. (1998). Mikhail Bakhtin: A theory of dialogue. Constellations, 5(3), 381-402.

Nikulin, D. (2006). On dialogue. Lexington Books.

Nikulin, D. (2010). Dialectic and dialogue. Stanford University Press.

That’s exactly why I love bringing experiential learning into my classes. It goes beyond worksheets and really taps into how students naturally learn...through doing, observing, and collaborating.

One of the best descriptions of learning's role in how we become who we become (in every way) - learning as the central dynamic of being human. I think you allude to but could more pointedly draw out how "shared learning" drove our evolution (https://tinyurl.com/2czy3som) and is WHY dialogue can be so powerful (consider also acknowledging Bohm on that https://tinyurl.com/y6xdee6g). While I truly appreciate the case you are making, the deeper issue for educators is understanding that how well - how healthily - learners learn is generally more relevant to their lives than what educators think they should learn in particular.