Why problems beat solutions

Teacher collaboration works better when educators study ongoing classroom challenges together instead of just looking for quick fixes.

Educational discourse has long been dominated by a relentless search for solutions—best practices, proven strategies, and silver-bullet interventions that promise to resolve the complex challenges of teaching and learning. Professional development sessions promise to deliver research-based strategies, district initiatives tout evidence-based programs, and educational conferences are filled with presentations on "what works" in teaching and learning. This solutions-oriented mindset reflects our institutional preference for clear, actionable guidance that can be systematically applied across diverse educational contexts.

However, mounting evidence from educational research suggests that this solutions-focused approach may be fundamentally misaligned with the nature of teaching itself. The problems of practice that teachers face—balancing individual and collective needs, managing competing curricular demands, fostering both support and challenge—don't simply disappear when we find the "right" approach. Instead, they persist, evolve, and require ongoing attention and navigation.

Recent scholarship from educational researchers like Mary Kennedy, Adam Lefstein, and organizational theorists like Smith and Lewis offers compelling evidence that the most productive path forward for educational collaboration lies not in the pursuit of universal solutions, but in the deep, sustained investigation of the problems themselves. By shifting our collaborative focus from solution-seeking to problem-understanding, we can create more authentic, contextually responsive, and ultimately more effective forms of professional learning and instructional improvement.

Persistent problems of teaching

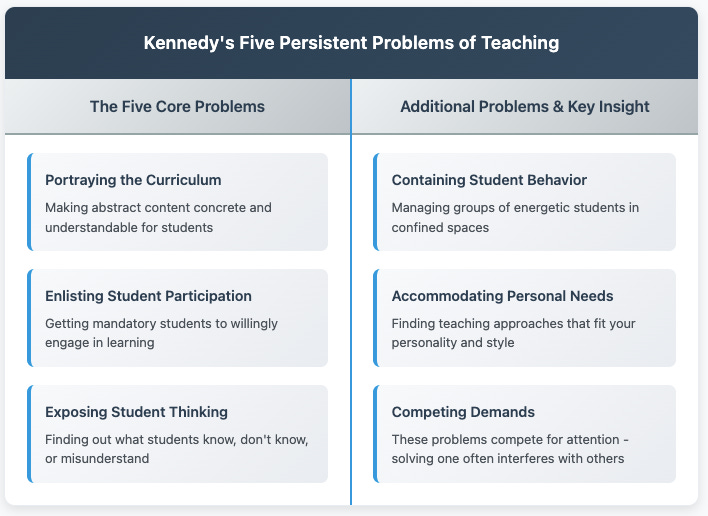

Mary Kennedy's analysis of teaching practice reveals a fundamental truth that challenges much of our conventional thinking about professional development: teaching involves persistent challenges that cannot be solved once and for all, but must be continuously managed and balanced. Kennedy identifies five enduring challenges that every teacher faces: portraying curriculum content in comprehensible ways, enlisting student participation, exposing student thinking, containing student behavior, and accommodating personal needs and teaching style. These are not temporary obstacles to overcome with the right training, but inherent features of the teaching role itself.

A teacher cannot "solve" the challenge of portraying curriculum content and then move on to other concerns. This challenge presents itself anew with each lesson, each group of students, and each piece of content to be taught. Moreover, these persistent challenges exist in dynamic tension with one another. A strategy that effectively engages student participation might simultaneously make it more difficult to maintain classroom order. An approach that beautifully portrays complex content might overwhelm students' cognitive capacity to engage meaningfully.

Kennedy argues that teachers make decisions roughly every two to three minutes during instruction, continuously monitoring different aspects of their practice and adjusting when something seems amiss. This constant decision-making requires sophisticated professional judgment about how different approaches address competing considerations and what trade-offs are involved in various responses to persistent challenges.

Rather than seeking collaborative processes that help teachers implement best practices, Kennedy's analysis suggests we need structures that help teachers develop deeper understanding of these persistent challenges and more sophisticated capacity to analyze and respond to them in context. This requires moving beyond "What works?" to more nuanced inquiries like "How do these different approaches address competing demands?" and "What are the trade-offs inherent in various responses?"

Investigating dilemmas

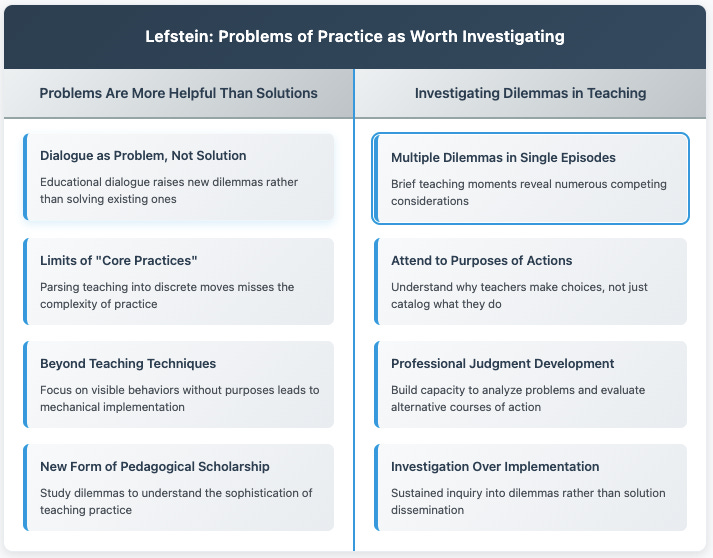

Adam Lefstein's analysis of classroom practice demonstrates that the dilemmas teachers face are not deficits to be corrected but complex problems worthy of sustained investigation. His work reveals how attempts to reduce teaching to a set of implementable techniques often miss the rich complexity that makes teaching both challenging and intellectually rewarding. When we focus on visible behaviors without attention to their purposes and contexts, we risk training teachers to implement techniques without understanding when, why, or how to adapt them.

In Lefstein's analysis of classroom practice, he identifies multiple dilemmas that emerge from even brief teaching episodes: tensions between reading comprehension and correct answer formation, challenges in managing discussions that build on student contributions, benefits and drawbacks of dramatic teaching approaches, and various strategies for handling disruptions. He doesn't present these as problems to be solved, but as ongoing challenges that reveal the sophistication of skilled teaching practice.

Lefstein advocates for "dilemma-driven analysis" that helps teachers develop analytical capacity to recognize, investigate, and thoughtfully navigate persistent tensions. This approach focuses on understanding the purposes that teaching behaviors serve rather than simply cataloging behaviors themselves. It examines how competing demands shape teaching decisions and resists reducing complex practice to simple best practices.

This suggests we should create opportunities for teachers to engage in sustained inquiry into the dilemmas they face. Rather than using collaborative time to disseminate best practices or troubleshoot implementation, we might collectively analyze classroom episodes, examine competing demands that shape teaching decisions, and develop shared frameworks for thinking about common challenges. The goal is helping teachers develop what Lefstein calls "professional judgment"—the ability to analyze problems and evaluate alternative courses of action in context.

Managing dynamic tensions

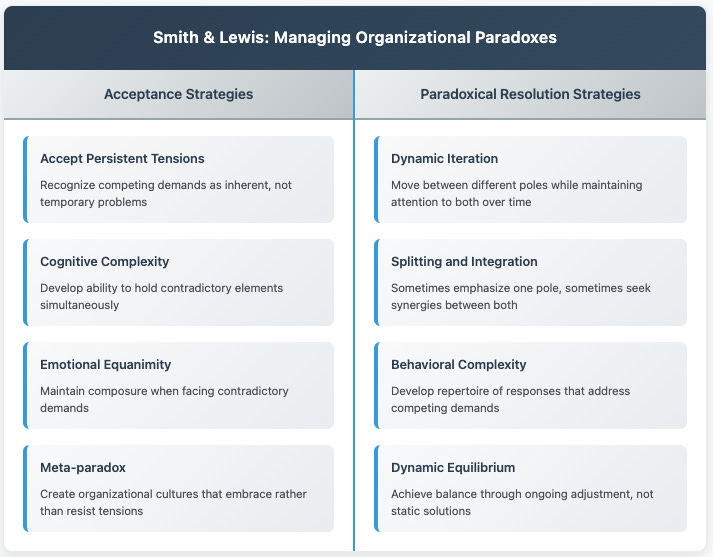

Organizational paradox theory from Smith and Lewis provides a framework for understanding why educational problems persist and how we might approach them more effectively. Their concept of "dynamic equilibrium" views teaching as managing ongoing tensions between competing yet interdependent demands, rather than resolving discrete problems. They identify paradoxes that manifest in education as persistent tensions between tradition and innovation, individual needs and collective management, teacher autonomy and systemic coherence, and academic achievement and broader developmental goals.

Paradox theory emphasizes "paradoxical resolution"—iterating between different approaches while maintaining attention to competing demands over time. Rather than seeking permanent resolution, effective practice requires dynamic navigation of persistent tensions. A teacher might shift between structured and open-ended approaches depending on context, while maintaining attention to both clarity and student exploration.

The theory distinguishes between "vicious cycles" from choosing one side of a tension rigidly, and "virtuous cycles" from "acceptance" of persistent tensions combined with dynamic management strategies. Acceptance means proactive recognition that tensions are inherent features requiring ongoing attention rather than permanent resolution. This enables "cognitive and behavioral complexity"—the capacity to navigate competing demands without becoming paralyzed by contradictions.

Paradox theory's "consistent inconsistency" suggests effective practice involves making different choices in different moments while maintaining coherent attention to multiple goals. This requires collaborative structures that normalize persistent tensions, provide opportunities to examine how different approaches address competing considerations, and support teachers in developing analytical and practical skills for dynamic, responsive practice.

Implications for practice

The insights from Kennedy, Lefstein, and Smith and Lewis point toward fundamental changes in how we approach educational collaboration and professional learning. Rather than designing processes around implementing best practices, we need structures supporting sustained inquiry into persistent problems and dilemmas that define teaching work. This requires both conceptual and practical changes in how we organize collaborative time and activities.

Conceptually, this means replacing deficit approaches that treat teaching challenges as problems to be solved with inquiry approaches that treat them as complex phenomena worthy of investigation. Rather than asking "How can we fix this?" collaborative inquiries might focus on "What competing demands are at play?" "How do different approaches address various considerations?" and "What can we learn from examining how this tension manifests in different contexts?"

Practically, this requires restructuring collaborative time to prioritize investigation over implementation. Instead of professional learning communities focused on data analysis and action planning, we might create inquiry groups engaging in dilemma-driven analysis of teaching episodes. Rather than lesson study cycles aimed at perfecting instructional sequences, we might develop protocols for examining teaching dilemmas, exploring how different approaches navigate competing priorities and what trade-offs they involve.

This problem-centered approach requires creating "safe spaces for productive struggle" with persistent challenges. Professional learning structures must normalize the persistence of challenges, provide opportunities for examining teaching dilemmas without judgment, and support teachers in developing sophisticated frameworks for analyzing complex professional situations. By embracing persistent problems rather than seeking to resolve them, educational collaboration can become more authentic, intellectually engaging, and ultimately more effective support for the complex work teachers do every day.

References

Kennedy, M. (2016). Parsing the practice of teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 67(1), 6-17.

Lefstein, A. (2009). More helpful as problem than solution: Some implications of situating dialogue in classrooms. In K. Littleton & C. Howe (Eds.), Educational dialogues: Understanding and promoting productive interaction. Taylor and Francis.

Lefstein, A., Israeli, M., Pollak, I., & Bozo-Schwartz, M. (2013). Investigating dilemmas in teaching: Towards a new form of pedagogical scholarship. Studia Paedagogica, 18(4), 10-32.

Smith, W. K., & Lewis, M. W. (2011). Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 381-403.

I really enjoyed this piece, Rod -- especially around the need for educators to navigate ever-present tensions in the work of teaching and learning that may be mitigated or confronted but that are never truly "solved."