Picture a contentious school board meeting: parents arguing about curriculum, teachers defending instructional methods, administrators presenting data, and community members raising concerns about values and tradition. Despite hours of discussion, little progress is made. Why? Often, these frustrating scenarios stem from participants engaging in fundamentally different types of argument without realizing it.

Aristotle identified three distinct forms of rhetoric: deliberative (focused on future decisions), judicial (examining past actions), and epideictic (ceremonial speeches celebrating values). In education, we frequently believe we're having a deliberative discussion about future policies while others are engaging in epideictic rhetoric about core values and identity. These mismatched purposes create talking past one another rather than productive dialogue.

Moreover, recent scholarship in epistemology - the study of knowledge and how we know what we know - suggests these communication breakdowns reflect deeper differences in how various stakeholders understand knowledge, learning, and evidence. Understanding these patterns can help educational leaders facilitate more productive discourse.

The knowledge problem in educational leadership

Thomas Kuhn's groundbreaking work on scientific paradigms offers valuable insights for education. Just as scientists working within different paradigms can struggle to find common ground, educational stakeholders often operate from fundamentally different frameworks about the nature and purpose of education.

Consider how a constructivist teacher views student engagement compared to an administrator focused on standardized outcomes. They may observe the same classroom but "see" entirely different things. The teacher might notice deep student discourse and emergent understanding, while the administrator sees off-task behavior and lack of clear learning objectives. Neither is necessarily wrong - they're operating from different paradigms about what constitutes learning.

This paradigm effect extends beyond classroom observation. It influences how we interpret data, what we consider valid evidence, and even what we mean by basic terms like "achievement" or "understanding." These aren't mere differences of opinion but reflect fundamental epistemological divisions about how we know what students know.

Furthermore, different stakeholder groups often bring different types of knowledge to educational discussions. Teachers bring practical classroom knowledge, researchers bring theoretical and empirical knowledge, parents bring contextual knowledge about their children, and administrators bring systemic knowledge about operations and policy. Each type of knowledge is valuable, but they can be difficult to reconcile.

Types of arguments in educational discourse

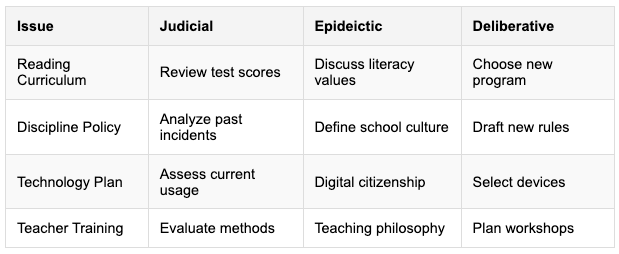

Understanding Aristotle's three types of rhetoric helps explain many common conflicts in educational settings. Deliberative rhetoric appears in discussions about policy changes, curriculum adoption, and resource allocation. These arguments focus on future consequences and practical outcomes. They typically involve claims about what will work best to achieve agreed-upon goals.

Judicial rhetoric surfaces in teacher evaluations, student discipline cases, and assessment of past initiatives. These arguments examine past actions and their consequences, often seeking to assign responsibility or learn from experience. They rely heavily on evidence and interpretation of past events.

Epideictic rhetoric manifests in mission statements, graduation speeches, and discussions of school values. While often dismissed as merely ceremonial, these arguments play a crucial role in establishing and maintaining shared values and identity. Many apparently practical debates actually mask deeper conflicts about values and identity.

These different forms of rhetoric require different types of evidence and different standards of evaluation. Problems arise when participants engage in different types of rhetoric without recognizing it. For example, a data-driven argument about instructional effectiveness (deliberative) may fail to address underlying concerns about school culture and values (epideictic).

Building shared understanding

Kuhn's concept of incommensurability suggests three specific barriers leaders must address. Methodological incommensurability occurs when groups use different standards to evaluate success. For instance, standardized test scores versus portfolio assessments represent fundamentally different approaches to measuring learning.

Observational incommensurability means different frameworks lead to different interpretations of the same events. A "disruptive" student might be seen as showing initiative or lacking discipline depending on one's pedagogical framework.

Semantic incommensurability arises when key terms carry different meanings across groups. "Rigor," "equity," and even "learning" often mean different things to different stakeholders.

Leaders can address these barriers by actively working to build shared vocabulary and frameworks. This might involve creating structured opportunities for different stakeholder groups to articulate their understanding of key concepts and examine their assumptions. It requires acknowledging that some differences in perspective may be fundamental rather than superficial.

Implications for practice

Educational leaders can improve discourse by explicitly identifying which type of rhetoric is appropriate for different discussions. Board meetings might need to separate policy discussions (deliberative) from values discussions (epideictic). Professional development might need to balance examining past practice (judicial) with planning future improvements (deliberative).

Leaders should acknowledge when different stakeholders are operating from different paradigms and help create bridges between these perspectives. This might involve using multiple forms of evidence and multiple frameworks for evaluation.

Creating structured opportunities to develop shared language and understanding is crucial. This could include professional learning communities that explicitly examine assumptions about teaching and learning, or community forums that explore different stakeholder perspectives.

The goal isn't to eliminate differences in perspective but to create productive dialogue across different ways of knowing and arguing. By understanding the epistemological roots of educational debates, leaders can better facilitate meaningful discussion and decision-making in their communities.

References

Aristotle. (trans. 2007). On Rhetoric: A Theory of Civic Discourse. Kennedy, G.A. (Trans.). Oxford University Press.

Kuhn, T. (1970). The nature of scientific revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago, 197(0).

Neta, R. (2024). Epistemology. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Rapp, C. (2024). Aristotle's Rhetoric. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Interesting application of Aristotle and Kuhn. It's interesting to note that Kuhn's theory about paradigms was inspired by his struggle with Aristotle's On Physics and in particular his understanding of motion.

I'm not sure that it the disagreement in education would be solved simply by being aware of the rhetorical space we are residing in. Personally I have found that in most conversations, beyond the purely pragmatic and operational, establishing the epideictic is an essential part of the process. Certainly, as a school leader, although I don't frame it in the ornate garb of Aristotle. I do always consider how to establish the epideictic parameters. To take a simple example, in talking to teachers about learning one has to tease our shared meaning, congruency if you will, between my understanding of learning and theirs. To fail to do that is to fail overall. It's why a critical part of the job of school leadership is the continual articulation of values in principle and in action. When I ran admissions meetings for prospective families one part of the communication I realized early on was expressing to families what the school actually set out to achieve and what it didn't. That I learned through paying attention each day to what was going on in every classroom and continually asking faculty, students and parents to explain particular concepts in their terms. You build up background knowledge (Kuhn's paradigm so to speak).