Which problems get attention?

Teaching's five core challenges hit differently with my students than when I used to analyze them as an education reformer.

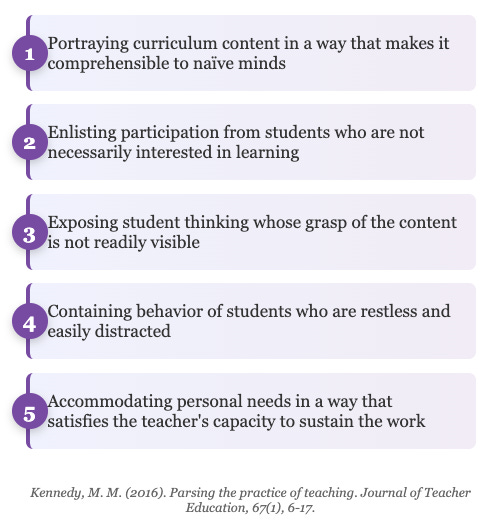

I’ve spent years thinking about teaching—studying it, writing about it, supporting teachers doing it. But this year, I’m back in my own classroom with 51 juniors in English 3, and the problems I used to analyze from a distance now greet me every single period. Mary Kennedy (2016) argues that teaching practice consists of five persistent challenges that all teachers must continually address: portraying curriculum, enlisting participation, exposing student thinking, containing behavior, and accommodating personal needs. These aren’t problems to be solved once and forgotten—they’re tensions to be managed constantly, in real time, with imperfect information and limited resources. What’s changed for me isn’t the nature of these problems, but my relationship to them.

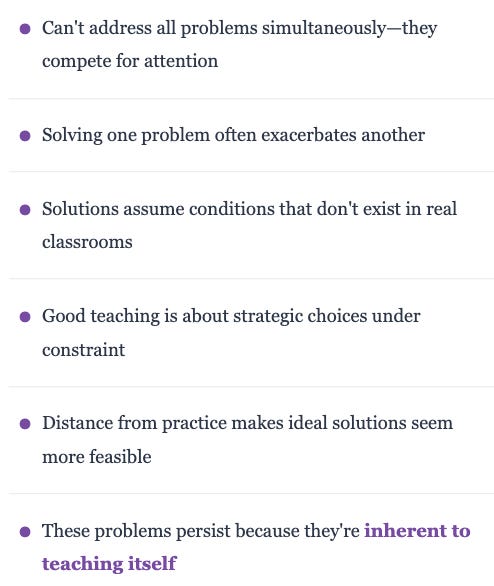

When you’re planning from outside the classroom, these problems seem solvable with the right systems, tools, or professional learning. When you’re inside it, managing 51 teenagers and their Chromebooks while trying to teach The Great Gatsby, you realize these challenges compete with each other for your attention. A solution to one problem can exacerbate another. A strategy that works beautifully one day might fail completely the next, with different students or different content.

This essay reflects on how my understanding of teaching’s core problems has shifted now that I’m navigating them daily rather than theorizing about them. I’m not offering solutions—I’m still figuring this out. But I am noticing patterns in what actually helps versus what sounds good in theory, and I’m developing a clearer sense of which problems deserve my limited attention at any given time.

Beautiful materials meet unprepared students

Kennedy (2016) describes portraying curriculum as the challenge of rendering “curriculum content in a way that makes it comprehensible to naïve minds” through live activities that unfold in real time and space. I used to think this meant creating excellent materials—pulling perfect excerpts from Gatsby, crafting thoughtful margin questions, designing text-dependent prompts that would guide students into close reading. The curriculum portrait seemed clear in my planning: here’s the text, here are the questions, here’s what rigorous analysis looks like.

What I’m learning is that a beautiful curriculum portrait means nothing if students lack the foundational knowledge to engage with it. The problem reveals itself differently across my classes. With my regular English 3 students, I want them to parse sentences into words, phrases, and clauses—to do the granular, sentence-level work that builds real comprehension. But I have to teach them what a clause is first. The curriculum portrait I envisioned assumes grammatical knowledge most of them don’t have. I’m stuck: I can’t do the close reading work without teaching grammar, but teaching grammar in isolation feels disconnected from the actual reading we need to do.

What I’m trying now is bringing more audio into the classroom—having students listen to passages as pre-work or alongside close reading exercises. I’m thinking about fluency routines, ways to make the language more accessible before asking students to take it apart. But I’m also recognizing that my previous assumption—that good curriculum design solves portrayal problems—was naive. Kennedy’s insight that portraits must be judged not by their elegance but by their comprehensibility to the actual students in front of you hits differently when those students are yours. The portrait has to match where students actually are, not where the standards say they should be. That requires constant adjustment, not just better materials.

The problem beneath the surface

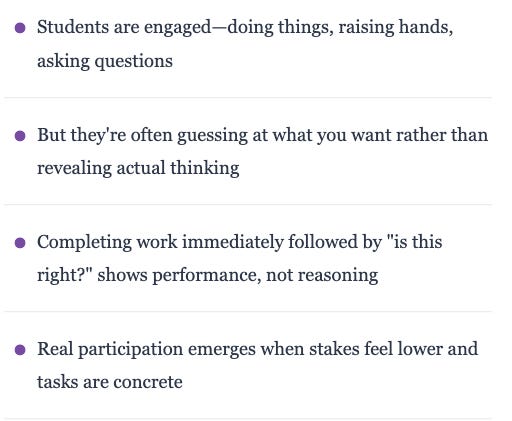

Kennedy (2016) reminds us that “education is mandatory but learning is not,” and that teachers belong to a class of “human improvement professions” where success depends entirely on clients’ willingness to improve themselves. I used to conceptualize participation problems as about engagement strategies—get students talking, use accountable talk, create collaborative structures. What I’m seeing is that the participation problem runs deeper. Students are often engaged—doing things, raising hands, asking questions. The problem is they’re not revealing their actual thinking. They’re guessing at what I want them to do.

This shows up constantly. A student completes a sentence correction exercise and immediately asks me to check it. Another writes a response to a prompt and wants to know if it’s “right.” They’re participating, but superficially—trying to figure out the game rather than engaging with the thinking. Sometimes the challenge is understanding the prompt itself. Sometimes it’s understanding the expectations for what a good response looks like. And with 51 students, I can’t individually check everyone’s work to clarify their uncertainty.

I’m experimenting with digital whiteboards where every student responds simultaneously, and quick polling to make everyone’s thinking visible at once. These tools help me see patterns—who’s confused, who’s getting it, what misconceptions are widespread. But they don’t solve the underlying problem: many students aren’t confident enough in their own thinking to commit to an answer without checking with me first.

The times I do get real participation—real thinking rather than guessing—it’s usually when the stakes feel lower and the task is concrete. Quick writes about personal connections to Frankenstein and discussions about AI and cloning generated authentic responses because students had opinions and experiences to draw on. They weren’t trying to figure out what I wanted; they were expressing what they actually thought. Kennedy’s point that students need to “actively think about” content to retain it (2016) suggests I need more tasks that feel like genuine inquiry rather than performance. But I haven’t figured out how to do that consistently, especially with technical skills like grammar and syntax analysis.

Patterns you’d never see

Kennedy (2016) identifies exposing student thinking as perhaps “the least apparent” challenge to policy makers and critics, who may not realize that if teachers don’t know what students understand at any given moment, they can’t know whether to repeat, elaborate, or move on. This resonates deeply with my current experience. Reading 51 exit tickets while planning tomorrow’s lesson means skimming for completion, not analyzing for patterns. You catch obvious errors, but you miss the subtle trends that reveal what students actually understand.

This is where technology has genuinely helped me see differently. Classroom polling tools let me collect responses quickly and identify trends I’d never catch manually. I can see at a glance where students are struggling with style application, what volume of work they’re producing, how they’re managing cognitive load. When I used AI tools to parse quick write responses about Frankenstein and artificial intelligence, I discovered patterns in how students were connecting the novel to contemporary issues—patterns that would have remained invisible if I’d just read through 51 individual responses looking for completion.

But exposing thinking and acting on what you expose are different challenges. I can see the patterns now. I know which grammatical concepts are widespread problems. I know which students consistently struggle with analysis versus summary. What I don’t always have is time to address what I’m seeing. Kennedy (1997) argues that the “connection between research and practice” often fails because research identifies problems without accounting for teachers’ practical constraints—the limited time, the competing demands, the impossibility of addressing everything simultaneously.

What I’m learning is that exposing student thinking isn’t just about assessment—it’s about making strategic decisions about which exposed problems to address and which to acknowledge but not act on immediately. I can’t fix everything I see. I have to choose.

The one-to-one problem

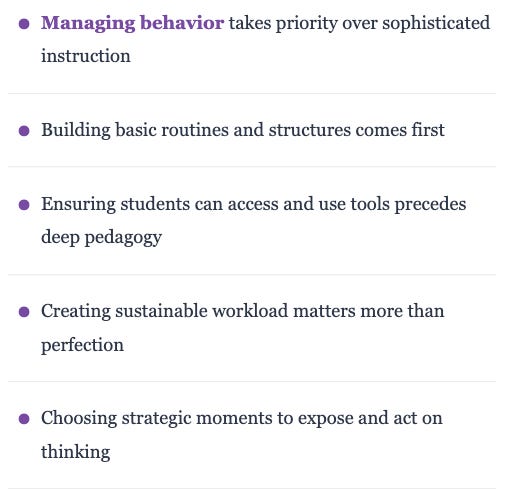

I used to work in environments where I controlled the technology. Chromebooks stayed in a cart. I managed charging and setup. Students got devices when I needed them to have devices. One-to-one computing sounded like progress—more access, more equity, more opportunity. What it actually means in my classroom is a constant management challenge that shapes every lesson I plan.

Students might not have chargers. Devices might not be charged. One platform might not work on one student’s device while working fine for everyone else. Different student groups have different access restrictions or blocking patterns I don’t control. And overwhelmingly, students want to find ways to play games and listen to music. If I need them on a platform to watch instructional videos, how do I block other activities? I can ask students to put Chromebooks “half-mast”—partially closed so I can monitor screens—but that assumes compliance, and compliance isn’t consistent.

Kennedy (2016) points out that containing behavior interacts with all the other challenges—you can’t address this one first and move on to the others. Device management and curriculum portrayal are completely entangled when every student has a device and you don’t control what’s on it. I can plan a beautiful lesson built around close reading of a digital text with annotation tools, but if five students can’t access the platform, three are playing games, and four are listening to music through one earbud while pretending to work, the lesson falls apart.

What I’m realizing is that device management isn’t a problem I can solve with better systems alone. It requires different lesson design—building in checkpoints, creating accountability structures, accepting that some activities just won’t work in a one-to-one environment. It also requires letting go of the idea that all students will be on-task all the time. Some containment is about preventing disruption to others’ learning, not ensuring perfect compliance from everyone.

Which problems get attention

The metaphor I keep returning to is spinning plates. Teaching feels like managing a dozen spinning plates while someone keeps handing you more. Every problem I’ve described—portraying curriculum, enlisting participation, exposing student thinking, containing behavior—is a plate. They’re all important. They’re all wobbly. You can’t keep all of them spinning perfectly at once.

Kennedy (2016) identifies accommodating personal needs as the fifth persistent challenge, arguing that teachers must find ways to address the other four challenges “in a way that is consistent with their own personalities and personal needs.” This is a topic we rarely address in teacher education, but it’s critical. If a teacher cannot create an atmosphere they’re comfortable living in, they won’t remain teaching long.

What’s changed for me isn’t that I’ve found balance—it’s that I’ve started making explicit choices about which plates get my attention when. Right now, I’m focusing on containing behavior. I’ve made some progress with seating charts, opening routines, and logical consequences that create accountability. Until I have basic behavioral structures in place, I can’t really address participation problems. Students won’t take risks with their thinking if the classroom environment feels chaotic.

This is where the “jobs to be done” framework helps me conceptualize my work differently. I’m not trying to do all the jobs of teaching equally well simultaneously. I’m picking a few jobs, focusing on those, and accepting that other important things will be incomplete or imperfect for now. That’s not failure—it’s sustainability. Kennedy (2016) argues that teachers must “continually re-think their solutions to these multifaceted challenges” because each new student, group, and topic requires new approaches. The alternative to strategic focus is burning out while trying to keep all the plates spinning and watching them all crash anyway.

Implications for practice

Kennedy (2016) argues that we need to stop parsing teaching into lists of discrete behaviors and instead help novices understand teaching as a practice that entails five persistent problems, each presenting difficult challenges, all competing for attention. Viewed this way, the role of teacher education is not to offer solutions to these problems, but to help novices learn to analyze these problems and evaluate alternative courses of action.

This shifts what instructional leaders and teacher educators should prioritize. First, professional learning needs to be grounded in these tensions, not in best practices that assume them away. Teachers need time and support to experiment with managing these problems in their specific contexts. Kennedy (1997) notes that the gap between research and practice often exists because we present solutions without helping teachers understand the problems those solutions address. Show me what participation looks like when students are uncertain about what you’re asking. Show me how you expose thinking when you have 150 students. Show me device management when you don’t control the devices.

Second, we need to stop pretending that good teaching means doing everything well simultaneously. Kennedy’s framework suggests that effective teachers make strategic choices about which aspects of their practice get intensive focus at different times. Instructional leaders could support this by helping teachers identify which problems most need attention in their specific context, rather than evaluating them against a rubric that assumes all problems are equally addressable at all times.

Third, technology solutions need to account for the reality that tools create new problems even as they solve old ones. One-to-one computing exposes student thinking in new ways—I can see patterns I’d never see otherwise. But it also creates behavior containment challenges that fundamentally reshape how I design lessons. Ed reformers advocating for technology access need to grapple with the management implications, not just the opportunity implications.

Fourth, curriculum design needs to account for the gap between beautiful materials and student readiness. Kennedy (2016) emphasizes that portraits must be “comprehensible to naïve minds,” not just elegant in their design. It’s not enough to create excellent resources. We need to think about what foundational knowledge students need to engage with those resources, and what we do when they don’t have it.

Finally, we need pedagogies in teacher education that help novices learn to reason about practice rather than merely prescribing behaviors. Kennedy (2016) argues that novices “cannot persist as teachers unless they find a way to address all five of these challenges,” and that “all of them are difficult, and all five are inherent to the work of teaching.” Our task isn’t to show them the one right way to teach, but to help them understand the persistent problems they’ll face and develop the analytical capacity to evaluate different approaches to those problems.

References

Kennedy, M. M. (1997). The connection between research and practice. Educational Researcher, 26(7), 4-12.

Kennedy, M. M. (2016). Parsing the practice of teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 67(1), 6-17.