What's Better Than Either Consensus or Dissent?

Agreement, disagreement, agreeing to disagree, and the purpose of meetings

I’ve been working through Littleton and Mercer’s Interthinking recently. I came across Mercer’s work through investigations into oracy, inspired by some Tweets on UK edutwitter. Aside from the reality that there’s so many terms for speaking and listening: oracy, orality, dialogism, to name a few; I was intrigued to find Mercer and others’ work situated in the Vygotskian tradition of “Through others we become ourselves”. Littleton and Mercer outline three distinct types of talk in Interthinking:

When I encountered this, my first thought was a connection to ideas I’d gathered from Nikulin’s Dialectic and Dialogue. It seems reasonable to draw a connection between disputational talk and dissensus, cumulative talk and consensus, and exploratory talk and allosensus. These terms only seem more complex than they truly are—dissensus connects with dissent or disagreement (disputation), consensus connects with agreement (cumulation), and allosensus connects with inquiry (exploration). Allosensus here may be the most obscure, perhaps this will help out:

Allosensus is a term used in describing the conclusion of a dialogue. Rather than consensus or dissensus, Allosensus retains disagreement, but recognizes the other participant in the dialogue as valid, and leaves open the potential for a continuation of the conversation.

I’ve been considering invitations to dissent or consent in the design and facilitation of teacher collaborative discourse. To expand—many times the system or structure of a collaborative meeting has a desired outcome of some sort, or at least an outlined protocol to follow with hope of an intended result. A collaborative team meeting under the auspices of a PLC may desire to reach consensus on the lesson plan and methods for upcoming work in their courses. A collaborative school leadership team meeting my desire to reach consensus about school improvement initiatives for the upcoming term. A collaborative group within the context of a course may desire to reach consensus about an argument they’re rendering, or a case they’re making.

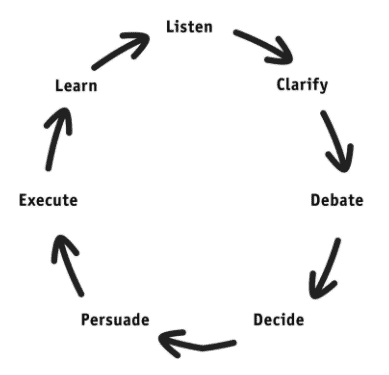

Oftentimes positional authority, organizational politics, or the realities of supervision and direct reporting affect the quality and character of collaborative discourse. It strikes me here that there’s a relationship between the purposes of meetings and the associated quality of discourse. I’ve been planning to write a little more about what Kim Scott has to say in Radical Candor about meetings and their purposes—those which are brainstorming and trouble-solving versus those which are decision-making oriented. She recommends separating them so that the pressures of decision-making (consensus) do not affect the sharing of ideas (allosensus).

I’ll dig more into the practicalities of that at another time, but I’ll close this out with a deeper dive into how Nikulin describes dialogue and its aspects in Dialectic and Dialogue. Nikulin lists these four components as those that “turn conversation into dialogue: personal other, voice, unfinalizability, and allosensus.”

Personal Other: “Dialogue, as a conversation with another person, always involves an expression of one’s personal other.” This is echoed in Bakhtin’s work on addressivity, or the necessity of us each to “answer” for our sociocultural position. This may be captured as well through the notion that utterances are by necessity formulated within a relationship to a language community, and for the interpretation of another person. In other words, utterances are both responses to our sociocultural moment, previous dialogue(s), and must to some extent anticipate or presage responses from an other.

Voice: “A single voice ‘alone in the desert’ is a contradictio in adiecto, a contradiction in terms: a voice must resonate with another voice. Thus the voice is a voice for the other and with the other.” Nikulin recognizes the import of gesture and other physical or embodied aspects of dialogue, but points out that dialogue can occur (consider telecommunication) without the present, embodied aspect.

Unfinalizability: “Dialogue is an exchange in which the participants can continue to converse with each other without ever exhausting their various relations either with themselves or with other persons.” Because of this “live” quality of dialogue, there’s always the opportunity for another utterance. This becomes fascinating considered in contrast to writing, monologue or dialectic. Further, the omnipresence of interruption and potential interruption is another marker of this unfinalizability—and something I’ll investigate further this year.

Allosensus: “Unlike both consensus and dissensus, allosensus is productive: it allows one to recognize the difference of and from the other through dialogical and unfinalizable unwrapping of the inexhaustible contents of one’s personal other.” Nikulin puts it a bit more succinctly and clearly as: “Consensus terminates the life of dialogue.”

Now, this final bit about allosensus was really complicated by something I just encountered in Littleton and Mercer’s Interthinking. They describe educational research in learning environments wherein discourse and collaboration or necessary, and they describe studies that have shown that seeking consensus—as a ground rule—has been demonstrated to bring about more exploratory talk. My first thought was to push back on this:

I suppose I had trouble with the phrasing of “only through consensus” here. But I do think it’s instructive to distinguish between seeking consensus and finding consensus. I think that’s the difference with allosensus, and it strikes me—at least intuitively—as workable. Seeking consensus invites me to more thoroughly consider the points of view, the personal others, of those with whom I’m in dialogue. Seeking helps us refine our views and claims, note potential gaps or pitfalls in our reasoning, and bring a bit of nuance to our work. Who wouldn’t want that to be the ultimate character of our teaching and learning work?