What educators should know about talking with one another

The quality of how educators talk with one another—not just what they say—directly shapes their thinking, their students' learning, and their school's capacity for improvement.

Every day, educators engage in countless conversations—discussing student progress in hallways, debating curriculum choices in team meetings, negotiating conflicts with colleagues, coaching one another through instructional challenges. We talk so much that conversation seems utterly mundane, hardly worth examining. Yet decades of scientific research across psychology, linguistics, and communication studies reveal something extraordinary: the quality of how educators talk with one another may be the most powerful yet overlooked determinant of student learning, professional growth, and organizational improvement. Most educators have received extensive training in how to talk with students but virtually none in how to talk with each other. This gap matters enormously because the conversations among adults in a school directly shape the conversations adults have with students, and ultimately, the thinking students develop.

The science of dialogue—drawing from cognitive psychology, discourse analysis, organizational communication, and philosophy of language—demonstrates that conversation operates according to principles most of us have never consciously considered. When we understand these principles, patterns that seemed mysterious suddenly make sense: why some team meetings energize while others drain, why certain coaching conversations transform practice while others accomplish nothing, why professional learning communities in one hallway thrive while those down the hall collapse. These aren’t matters of luck or personality; they reflect whether the conversations align with or violate fundamental principles of how human dialogue actually works. Ignorance of these principles doesn’t make them less operative—it just means we violate them unconsciously, wondering why our well-intentioned efforts at collaboration so often disappoint.

What follows synthesizes insights from multiple scientific disciplines into practical understanding for educators. The goal isn’t to make conversation feel artificial or overly technical—quite the opposite. Understanding how dialogue works enables us to have better conversations more naturally, to recognize what’s happening when conversations go well or poorly, and to deliberately create conditions where productive talk becomes routine rather than exceptional. These aren’t tips and tricks but fundamental principles that, once understood, change how you experience every professional conversation. For teachers and educational leaders committed to continuous improvement, understanding dialogue isn’t optional professional development—it’s foundational to everything else we’re trying to accomplish together.

Your brains automatically sync

When you engage in genuine conversation with a colleague, something remarkable happens beneath the surface of your awareness: your brain begins automatically synchronizing with theirs at multiple levels simultaneously. Research by Garrod and Pickering (2004, 2009) reveals that conversational partners unconsciously align their vocabulary choices, grammatical structures, speech rates, and even body postures within moments of beginning to talk. If your teammate describes a student as “struggling with executive function,” you’ll likely adopt that exact phrase rather than your preferred “having trouble with organization”—not because you’re being polite but because your cognitive system automatically aligns with conversation partners. This isn’t superficial mimicry; it’s a fundamental mechanism through which human beings achieve mutual understanding. Without this automatic alignment, genuine comprehension would be nearly impossible.

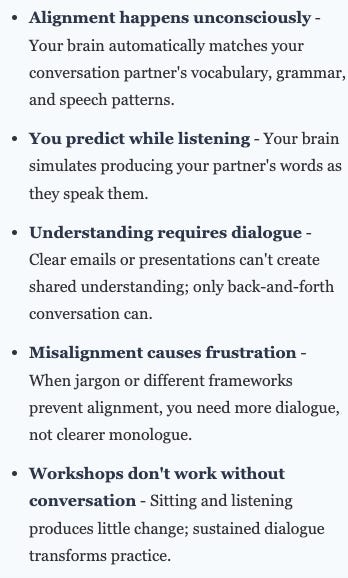

The science explains why this happens by revealing what your brain does while listening. You’re not passively receiving and decoding your colleague’s words like a computer processing input. Instead, your brain actively predicts what she’ll say next by covertly simulating the production of her utterance using your own language systems—essentially, you’re internally “rehearsing” speaking her words as she speaks them. This is why you can often complete each other’s sentences, why conversation partners take turns with near-zero gaps (average 200 milliseconds between speakers), and why genuine dialogue feels qualitatively different from waiting for your turn to talk. When alignment is working well, conversation flows effortlessly; you understand not just the words but the intentions, implications, and unstated assumptions. When alignment fails—perhaps because someone uses unfamiliar jargon or speaks from a radically different framework—conversation becomes laborious, misunderstandings multiply, and frustration builds.

You cannot achieve genuine shared understanding without actual back-and-forth dialogue.

Here’s what this means for your daily practice: You cannot achieve genuine shared understanding without actual back-and-forth dialogue. The carefully crafted email explaining your perspective, the detailed presentation of your idea, the eloquent articulation of your vision—none of these creates alignment, no matter how clear they seem to you. Alignment requires the interactive, predictive, mutually-adjusting process that only happens in real conversation. This is why the colleague who seemed to understand your explanation perfectly reveals a completely different interpretation when you check back later. This is why professional development workshops where participants sit and listen produce so little change—there’s no opportunity for alignment. This is why the most effective teacher teams are those with time for sustained dialogue, not just information sharing. When you find yourself thinking, “Why don’t they get what I’m saying?”—the answer is almost always: insufficient dialogue. You need more conversation, not clearer monologue.

Thinking is made of conversations

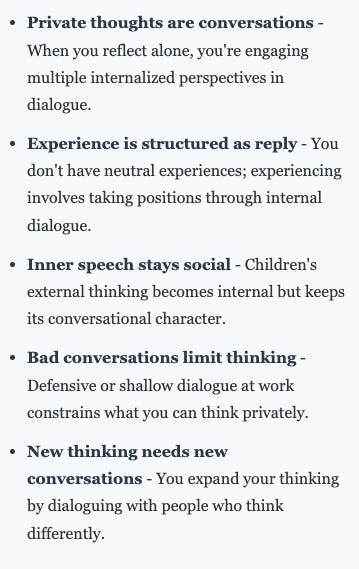

The most profound insight from dialogue science challenges something you probably take for granted: the nature of your own thinking. When you’re alone, driving home from school and mentally replaying a difficult parent conversation, or lying awake rehearsing tomorrow’s meeting with your principal, what exactly is happening in your mind? Common sense suggests you’re accessing your private thoughts, the inner mental world that exists independent of others. But research in developmental psychology and discourse analysis reveals something quite different: your thinking itself is structured as dialogue, built from internalized conversations with others. When you reflect on that parent meeting, you’re not neutrally reviewing facts; you’re engaging multiple perspectives in dialogue—imagining the parent’s point of view, hearing your principal’s likely response, arguing with your colleague’s earlier criticism, reassuring yourself from your mentor’s supportive stance. Even your private thoughts are populated by others’ voices.

This dialogical structure of thinking emerges from how human cognition develops. Young children think aloud; their problem-solving is transparently social and conversational. Gradually this external dialogue becomes abbreviated and internalized into what psychologist Lev Vygotsky called “inner speech”—but crucially, it retains its dialogical character. Your mature thinking still operates through position-taking, responding, anticipating reply, and engaging multiple perspectives, just as external dialogue does. Haye and Larrain (2012) argue that experience itself “has the structure of the reply”—you don’t simply have experiences and then think about them; rather, experiencing anything involves taking a position toward it in internal dialogue. When you feel excited about a new instructional approach, that excitement isn’t pre-linguistic emotion later translated into words; the feeling emerges through your internal dialogue comparing this approach to alternatives, imagining student responses, anticipating colleague reactions. Your emotions, perceptions, and thoughts are all constituted dialogically.

The quality of actual conversations you participate in directly shapes the quality of thinking you’re capable of.

What this means practically: The quality of actual conversations you participate in directly shapes the quality of thinking you’re capable of. If you work in an environment where conversations are consistently defensive, shallow, or compliance-focused, your internal dialogue becomes similarly constrained—you literally lose the capacity to think certain thoughts because you’ve never dialogically inhabited those perspectives with others. Conversely, when you regularly engage in conversations that are intellectually challenging, emotionally safe enough for genuine disagreement, and inclusive of diverse perspectives, your thinking becomes more sophisticated because your internal dialogue includes these perspectives. This is why isolation is so intellectually dangerous for educators—without rich dialogue, our thinking narrows. This is why the most effective professional learning involves sustained conversation with people who think differently than you do. This is why reflective practice requires not just solitary journaling but dialogical partnerships. You become capable of new thinking not primarily by acquiring new information but by participating in new kinds of conversations that expand your dialogical repertoire.

Words create reality

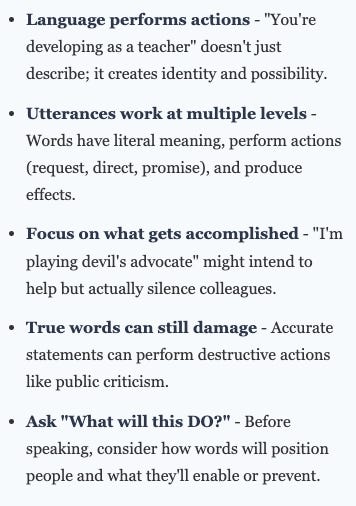

The third crucial principle concerns what happens when you speak. We typically assume language works representationally: words describe pre-existing thoughts, convey information about reality, report on the world as it is. But dialogue science, drawing from speech act theory and discourse analysis, demonstrates that language is fundamentally performative—utterances don’t just describe reality, they actively construct it. When you say to a struggling colleague, “You’re really developing your questioning skills,” you’re not merely reporting an observation; you’re performing an identity-conferring act that may reshape how your colleague sees herself and what becomes possible for her development. When your principal announces, “We are a professional learning community,” that statement isn’t describing existing reality but attempting to create that reality through the utterance itself. Every time you talk with colleagues, you’re not just exchanging information—you’re constructing the social reality you all inhabit.

This performative dimension means every utterance operates at multiple levels simultaneously. There’s the literal content (what the words denote), but there’s also the action being performed (asserting, questioning, directing, promising, warning), and there’s the effect produced (intended or otherwise). When your department chair says, “We need to align our assessments,” she might be asserting a fact, issuing a directive, making a request, or expressing frustration—and which action she’s performing dramatically affects what the utterance accomplishes. Philosopher William Abraham (1988) argues we must study not just what speakers intend but what their utterances achieve—the actual social actions accomplished through talk. A well-intentioned statement like “I’m just playing devil’s advocate” might intend to stimulate critical thinking but achieve the effect of silencing less confident colleagues. A principal’s “My door is always open” might intend to convey accessibility but achieve the effect of placing the burden entirely on teachers to initiate difficult conversations.

You must develop sensitivity to what your words do, not just what they mean.

What this means for your conversations: You must develop sensitivity to what your words do, not just what they mean. When you leave a conversation asking “How did that go?” you’re unconsciously asking what got accomplished: Was trust built or eroded? Were possibilities opened or foreclosed? Were relationships strengthened or damaged? Did we construct shared understanding or reinforce our separate realities? This performative awareness explains several common conversational failures. Sometimes technically accurate statements accomplish disaster—the words were precisely true but the action performed (say, public criticism) was destructive. Sometimes vague or even contradictory statements succeed brilliantly—they performed necessary actions like preserving relationships or maintaining productive ambiguity during uncertainty. Becoming skillful in dialogue requires moving beyond naive focus on “clear communication” toward sophisticated awareness of performative effects. Before speaking in consequential moments, ask yourself not just “Is this true?” but “What will this do?”—how will it position people, what actions will it enable or constrain, what reality will it help construct?

Implications for practice

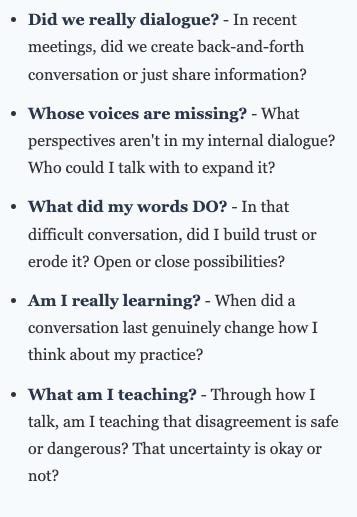

Understanding dialogue science points toward concrete changes in how you approach conversations with colleagues, starting with the most fundamental shift: treat dialogue as skilled practice worthy of deliberate development, not just something that happens naturally. Just as you wouldn’t expect to teach effectively without training in pedagogy, you shouldn’t expect to collaborate effectively without developing dialogical capacity. This means making the invisible visible—naming the moves that distinguish productive from unproductive dialogue. In your team meetings, occasionally pause to notice: Are we genuinely building on each other’s ideas or serially presenting separate viewpoints? Are questions asked to understand or to rhetorically position? When disagreement surfaces, do we explore it or smooth it over? Are we achieving alignment through dialogue or just assuming alignment from silence? Many teams operate for years without ever explicitly discussing how they talk with one another, then wonder why collaboration feels forced or fruitless.

The second practical implication: create structures and protocols that scaffold productive dialogue until new habits form. Left to default patterns, conversations tend toward the familiar and comfortable, which often means superficial or defensive. Protocols—structured processes for dialogue—aren’t bureaucratic constraints but cognitive tools that enable conversations we wouldn’t naturally have. A protocol that requires presenting student work before discussing it prevents the common pattern of abstract theorizing disconnected from evidence. A protocol ensuring every voice is heard before discussion begins prevents the dominant voices from setting frames that others then merely react to. A protocol for examining dilemmas rather than solving problems creates space for the complexity that quick problem-solving erases. These structures feel artificial initially because they’re interrupting automatic patterns, but they’re working with how dialogue actually functions—creating conditions for alignment, expanding dialogical perspectives, and making performative effects more conscious. As new patterns become habitual, protocols can fade, having accomplished their developmental purpose.

The third crucial practice: recognize that every conversation is simultaneously accomplishing its immediate purpose and teaching participants how to think together. When you lead a grade-level meeting, facilitate a coaching conversation, or participate in a leadership team discussion, you’re not just addressing the topic at hand—you’re modeling and reinforcing norms about dialogue itself. If you genuinely listen even to ideas you disagree with, you teach that disagreement is safe. If you make your thinking visible through talk rather than just announcing conclusions, you teach that reasoning matters, not just results. If you name confusion or uncertainty rather than projecting false confidence, you teach that learning is ongoing. Conversely, if you subtly punish dissent, perform listening while waiting to speak, or treat questions as challenges, you teach colleagues that dialogue is dangerous. The most important question for any educator interested in improving professional culture thus becomes: What are my conversations teaching people about thinking, relating, and constructing shared reality? This awareness transforms how you participate in every professional interaction, recognizing each conversation as opportunity to strengthen or weaken your collective capacity for the dialogue that improvement requires.

References

Abraham, W. J. (1988). Intentions and the logic of interpretation. The Asbury Theological Journal, 43(1), 11-25.

Fairhurst, G. T., & Connaughton, S. L. (2014). Leadership: A communicative perspective. Leadership, 10(1), 7-35.

Garrod, S., & Pickering, M. J. (2004). Why is conversation so easy? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(1), 8-11.

Garrod, S., & Pickering, M. J. (2009). Joint action, interactive alignment, and dialog. Topics in Cognitive Science, 1(2), 292-304.

Haye, A., & Larrain, A. (2013). Discursively constituted experience, or experience as reply: A rejoinder. Theory & Psychology, 23(1), 131-139.

This is a great summary of why moving schools or districts is an underrated professional learning opportunity. It's also not without risk if you don't know what the conversations are like at the new site...

Educators are too often cut off from each other.

If you’re looking for accessible, research-based information that slices through the endless loads of overly worded baloney, I would encourage you to subscribe to my free Substack, The Reading Instruction Show.

Substack

https://thereadinginstructionshow.substack.com/

Andy Johnson