What does anyone mean by curriculum?

Curriculum means different things to different stakeholders, creating tensions leaders must navigate thoughtfully.

When I stepped into my first leadership role in education, I naively believed that "curriculum" was a straightforward concept—simply the content we teach students. Years of navigating curriculum debates, implementation challenges, and reform initiatives have taught me otherwise. The term "curriculum" carries with it contested meanings that significantly impact how we approach educational leadership, policy, and classroom practice. These different understandings often operate beneath the surface of our discussions, causing misalignments and miscommunications that can derail even the most well-intentioned initiatives.

This contested nature of curriculum isn't merely an academic concern—it has profound practical implications. When a district administrator views curriculum as a standardized document to be faithfully implemented while teachers see it as a flexible framework to be adapted to student needs, conflict is inevitable. Similarly, when policymakers focus exclusively on content standards while community stakeholders emphasize the lived experiences of students, we talk past each other rather than finding common ground. Understanding these different perspectives is essential for building the shared vision necessary for meaningful educational improvement.

In this exploration, we'll examine three different perspectives on curriculum that highlight its complexity and contested nature. Drawing from both academic literature and practical experience, we'll consider how these different frameworks influence our approach to educational leadership. By the end, I hope to demonstrate that acknowledging and navigating these different understandings isn't just an intellectual exercise—it's a fundamental leadership competency for anyone serious about educational transformation. The way we conceptualize curriculum shapes everything from classroom practice to system-wide reform efforts, making this conversation essential for all educational leaders.

Beyond official documents

Brad Gobby's exploration of curriculum provides a powerful expansion of our understanding, challenging leaders to think beyond official documents. Gobby identifies six distinct types of curriculum, including the official curriculum (formal documents like standards), the enacted curriculum (how teachers interpret and implement those documents), and the hidden curriculum (implicit lessons taught through school structures and routines). Perhaps most importantly, he emphasizes the concept of "curriculum as the lived experience of learners in a learning setting, whether or not those experiences are planned." This perspective radically broadens our understanding, positioning curriculum not just as what we intend to teach, but as everything students actually experience in educational settings.

This expanded view has significant implications for how we understand educational inequality and disadvantage. Gobby argues that social, cultural, political, and economic forces significantly shape the curriculum experiences of learners. For example, he notes how children from disadvantaged backgrounds often encounter a curriculum that fails to recognize their strengths and experiences, instead positioning them as deficient. Similarly, cultural diversity is frequently treated as exotic or inferior rather than as a valuable resource for learning. These dynamics reveal how curriculum, broadly understood, becomes a mechanism through which social inequalities are either reinforced or challenged.

The role of educators as "intellectual workers" becomes crucial within this framework. Rather than mere implementers of predetermined content, educators are positioned as critical thinkers who must question the assumptions embedded in their practice. Gobby challenges educators to ask probing questions like "Why do we think and do things like this?" and "What do my choices enable and constrain?" This stance requires moving beyond seeking quick fixes or "tips for teachers" to engage in the difficult intellectual work of analyzing how curriculum choices shape student experiences. For educational leaders, this means creating conditions that support teachers in this reflective practice while acknowledging the complex forces that shape curriculum experiences.

From content to method

Kieran Egan offers a historical perspective that illuminates how our understanding of curriculum has evolved over time and continues to shape current debates. Tracing the etymology of "curriculum" from its Latin roots through its historical usage, Egan demonstrates how the concept gradually shifted from referring to the temporal space of learning (the "container") to the content itself (what is contained). Throughout much of educational history, curriculum primarily concerned what should be taught, with questions of method remaining secondary. However, Egan identifies a profound shift that occurred during the 18th and 19th centuries, when methodological questions began to gain prominence, eventually transforming how we understand curriculum.

This historical shift was driven by both practical innovations and philosophical developments. Egan details how educators like Pinel, Itard, and Seguin, working with deaf-mutes and the "wild boy of Aveyron," focused primarily on how to teach rather than what to teach due to the unique needs of their students. Simultaneously, Rousseau's philosophy that "man is born free" and children are naturally good led to new approaches emphasizing methods that allow for natural development. These influences gradually moved from the margins to the mainstream of education, culminating in progressive movements that prioritized children's interests and development over specific content knowledge. This historical progression helps explain why methodology often dominates current curriculum discussions.

The consequence of this historical evolution, according to Egan, is a profound confusion about what curriculum actually is. Once curriculum expanded to include methodological questions, it lost clear boundaries as a field of inquiry. This expansion coincided with what Egan calls a "failure of nerve"—a loss of confidence in specifying what should be taught and why. He argues that rapid societal change has been used to justify avoiding content decisions ("Who can specify what skills will be needed in the future?"), leading to a situation where procedural concerns overshadow substantive ones. This historical perspective illuminates why curriculum debates often feel so disoriented, with stakeholders operating from fundamentally different assumptions about what curriculum even is.

Curriculum as philosophy

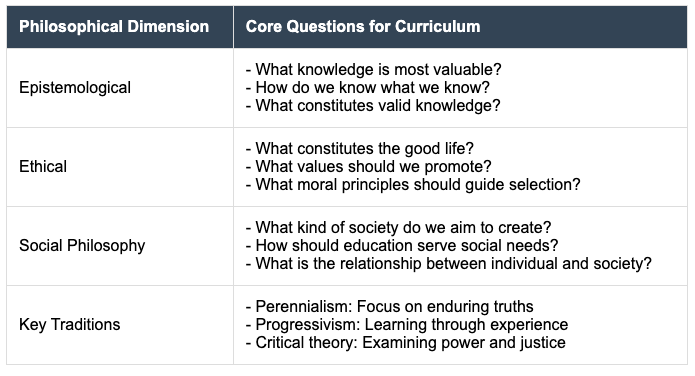

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy offers a third perspective on curriculum, framing it as fundamentally philosophical in nature, with curriculum decisions inherently involving questions of epistemology, ethics, and social philosophy. This philosophical approach reminds us that curriculum is not merely a technical exercise but reflects deeper questions about what knowledge is most valuable, what constitutes the good life, and what kind of society we aim to create. The encyclopedia entry examines various philosophical traditions that have influenced curriculum thinking, from perennialism's focus on enduring truths to progressivism's emphasis on learning through experience, highlighting how different philosophical commitments lead to radically different curriculum approaches.

Central to the Stanford perspective is the recognition that curriculum involves choices about whose knowledge is legitimized and whose is marginalized. Drawing on critical theorists like Michael Apple and Paulo Freire, the encyclopedia examines how curriculum serves as a form of "cultural politics" that can either reproduce or challenge existing social hierarchies. This critical lens reveals how seemingly neutral curriculum decisions—which subjects receive the most time, whose perspectives are included in textbooks, what forms of assessment are privileged—reflect power relationships and social values. The encyclopedia discussion of the "hidden curriculum" demonstrates how schooling transmits implicit lessons about authority, social relations, and what counts as legitimate knowledge, often reinforcing dominant cultural norms and expectations.

The Stanford entry also addresses contemporary philosophical debates about curriculum, including tensions between standardization and diversity, global and local knowledge, and traditional and progressive approaches. It explores philosophical questions raised by multiculturalism and postmodernism, which challenge universal curriculum narratives and emphasize multiple perspectives and ways of knowing. These philosophical debates are not abstract academic exercises but have concrete implications for how we conceptualize educational aims and design learning experiences. By foregrounding the philosophical dimensions of curriculum, the Stanford perspective reminds educational leaders that curriculum decisions are ultimately value decisions that cannot be resolved through technical or empirical means alone.

Leading in the curriculum crossfire

The first implication for educational leaders is the need to develop a comprehensive understanding of curriculum that acknowledges its multiple dimensions. Rather than limiting our focus to official documents, we must attend to the enacted, hidden, null, negotiated, and emergent aspects of curriculum that shape student experiences. This means looking beyond superficial implementation measures to examine how curriculum choices actually impact different student populations. When evaluating curriculum initiatives, leaders should ask: How does this affect the lived experiences of our most vulnerable students? What implicit messages are conveyed through our implementation approaches? What knowledge and perspectives are being prioritized or marginalized? This broader framework allows us to address educational inequities that might remain invisible when curriculum is viewed narrowly.

Leaders must also recognize curriculum as a historically and philosophically contested space where different stakeholders bring competing visions and values. This requires developing the capacity to mediate these tensions productively rather than ignoring them. When introducing curriculum reforms, leaders should anticipate resistance not just as implementation challenges but as expressions of deeper value conflicts that need acknowledgment and discussion. This might involve creating structured opportunities for stakeholders to articulate their curriculum assumptions and concerns, building deliberate alignment of purpose before diving into implementation details. Leaders who can navigate these contested spaces—helping communities find common ground while acknowledging legitimate differences—will be more successful in sustaining meaningful educational improvement.

Finally, educational leaders must position teachers as intellectual workers who actively interpret and adapt curriculum rather than simply deliver it. This means creating organizational conditions that support teacher agency and reflective practice while providing appropriate structures and guidance. Professional learning communities should focus not just on implementation fidelity but on critically examining curriculum assumptions and impacts. Leaders can model this intellectual stance by publicly wrestling with curriculum questions and acknowledging the complexity involved. This balanced approach—what Egan might call attending to both the "what" and "how" questions of curriculum—requires resisting both rigid standardization and complete relativism. By fostering a culture that values both educational purpose and professional judgment, leaders can help reconcile the tension between clear direction and local adaptation that lies at the heart of curriculum leadership.

References

Egan, K. (2003). What is curriculum? Journal of the Canadian Association for Curriculum Studies, 1(1), 9-16. (Originally published in Curriculum Inquiry, 8(1), 66-72, 1978).

Gobby, B. (n.d.). What is curriculum? In Understanding curriculum (pp. 5-29). Oxford University Press.

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (n.d.). Philosophy of education: Curriculum theory and practice. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/education-philosophy/

Great post!