Teach writing rather than just assign it

While K-12 schools excel at giving writing assignments, they rarely teach students the actual skills needed to write well.

Too often in K-12 education, we assign writing rather than teach it. Students receive prompts, rubrics, and deadlines, but rarely receive explicit instruction in the fundamental skills needed to construct coherent, persuasive writing. This practice reflects a deeper confusion about what writing instruction actually entails and how students develop as writers.

Our classrooms are filled with well-intentioned educators who genuinely want students to succeed, yet many struggle to move beyond simply evaluating writing to actually teaching the component skills that make writing effective. We've created a system where students are expected to intuitively grasp complex writing processes through repeated exposure rather than through systematic instruction.

The result is predictable: students who can follow formulas but cannot adapt their writing to new contexts, who can complete assignments but struggle to communicate effectively in authentic situations. Insights from educators Doug Lemov and Sarah Tantillo illuminate both the depth of our instructional confusion and potential pathways toward more effective writing instruction that actually prepares students for real-world communication.

Claims and questions

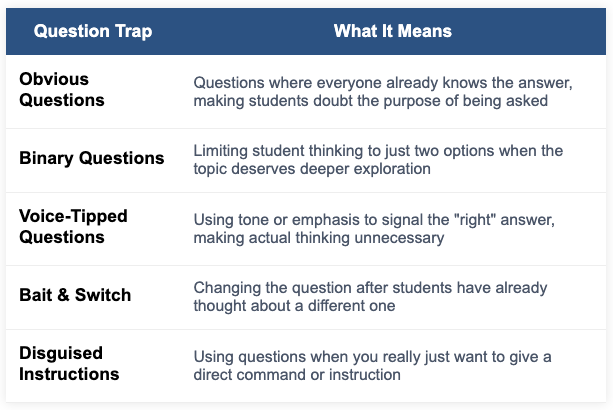

Much of our writing instruction centers on asking students to make claims, yet we fundamentally misunderstand when and how claims should be generated. Lemov's research on questioning reveals that we frequently fall into the "obvious trap," posing questions with self-evident answers and then demanding that students construct arguments around these non-debatable points. This creates an artificial writing situation that mirrors nothing students will encounter in authentic contexts.

A recent classroom example illustrates this confusion perfectly: students were asked to make a claim about the narrative structure of The Great Gatsby—not about its effects or significance, but simply about the structure itself. This assignment asks students to argue about something that can be objectively identified and described. A novel either is in first person or it isn't. These are matters of literary fact, not opinion, yet students were expected to construct arguments around them as if they were debatable propositions.

This misuse of "claim-making" reflects our broader confusion about academic discourse. As Lemov notes, "Questions with obvious answers are killers of intellectual culture because they pretend to ask a question when there's really no question." When students repeatedly encounter meaningless argumentative tasks, they learn to distrust both our instruction and their own understanding, approaching writing as a guessing game rather than authentic communication.

The artificial framework problem

Perhaps nowhere is our instructional confusion more evident than in our reliance on acronyms like CER (Claim, Evidence, Reasoning). These frameworks artificially separate elements that effective writers naturally integrate, creating unnecessary cognitive load while teaching habits that students must later unlearn. The treatment of claim, evidence, and reasoning as distinct, separable components reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of how writing actually works.

The Gatsby example demonstrates how CER frameworks lead us astray. When students are forced to make claims about factual literary elements, they must artificially construct arguments where none should exist. The resulting writing becomes tortured and unnatural, as students struggle to argue about objective features of the text. This approach teaches students to see argument where analysis or explanation would be more appropriate.

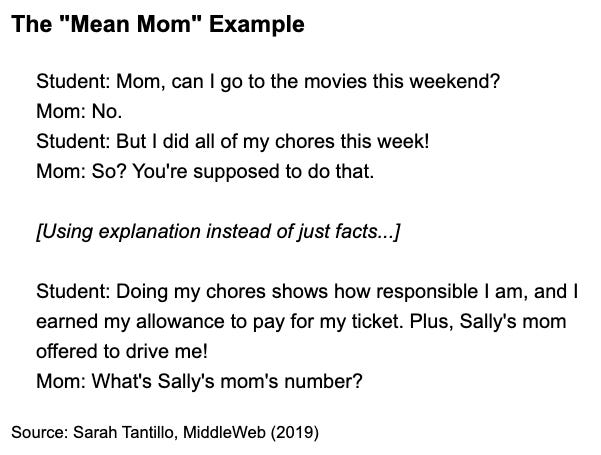

Tantillo's work reveals the futility of these artificial separations. In her "Mean Mom" example, she demonstrates how effective persuasion naturally weaves together facts and explanation, showing students that rigid distinctions between evidence and reasoning create mechanical rather than persuasive writing. Real writers don't think in terms of separate CER components; they think about how to use information effectively to serve their purposes—whether that purpose is to argue, explain, analyze, or describe.

Reducing cognitive load to build skills

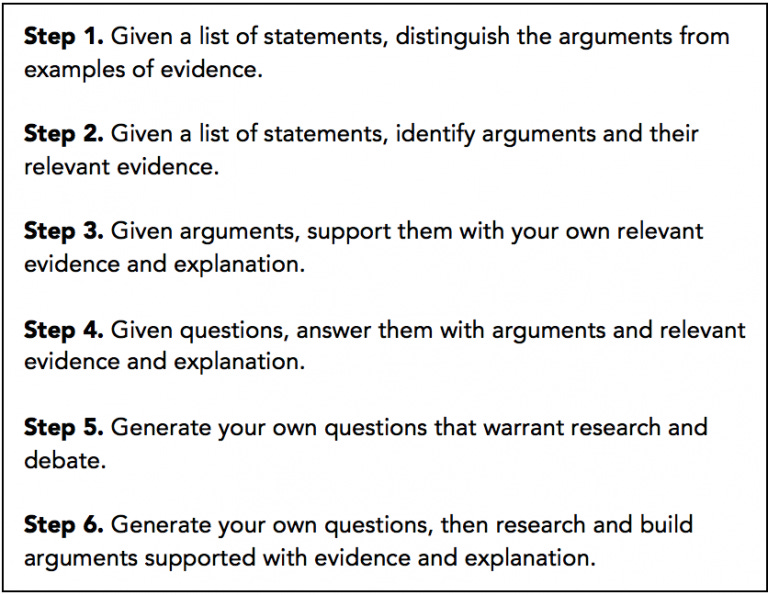

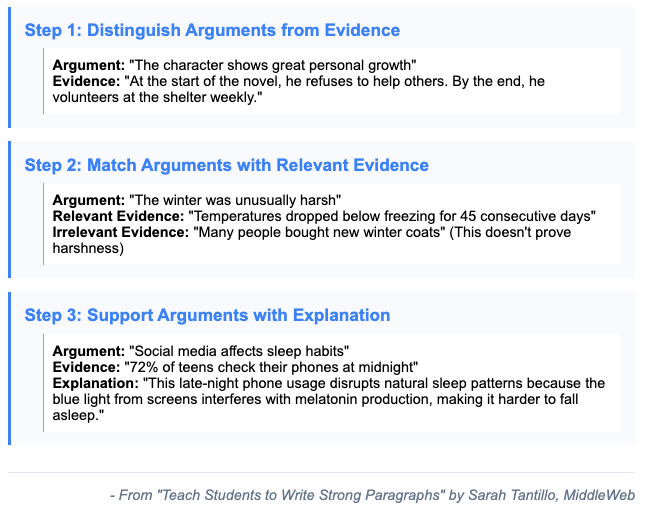

Tantillo's approach to paragraph instruction offers a more promising method that acknowledges the complexity of writing while providing appropriate scaffolding. By supplying topic sentences and teaching evidence selection explicitly, she reduces cognitive load while building authentic writing skills. This method recognizes that writing involves multiple complex processes that shouldn't be tackled simultaneously, especially for developing writers.

Her paragraph response technique demonstrates how we can teach writing systematically without relying on artificial frameworks. Students learn to integrate evidence naturally, develop explanations that serve their purposes, and construct coherent paragraphs that mirror authentic academic discourse. Rather than forcing students through the artificial CER sequence, this approach shows them how effective writers actually combine these elements fluidly.

Most importantly, Tantillo's method addresses what she identifies as "Step 2.5"—teaching students to evaluate and select effective evidence before asking them to use it. This explicit instruction in evidence selection fills a crucial gap in our instruction, helping students understand not just what evidence is, but how to choose evidence that actually supports their developing ideas, whether those ideas are claims, explanations, or analyses.

Implications for practice

We must fundamentally rethink our approach to writing instruction, moving from assignment to teaching. This means abandoning both the obvious questioning that Lemov identifies and the artificial frameworks that fragment the writing process. Instead, we need instruction that mirrors how effective writing actually works in authentic contexts, recognizing that not every writing task requires a claim.

Teachers need professional development that helps them understand how writing actually functions and how to teach it effectively. This includes learning to distinguish between situations that call for argument versus those that require explanation or analysis, understanding when claims are appropriate versus when other forms of discourse are needed, and developing the ability to teach evidence selection and integration without relying on formulaic CER approaches.

The ultimate goal must be preparing students for authentic writing situations they'll encounter beyond our classrooms. A student analyzing Gatsby's narrative structure in college wouldn't be expected to argue about whether it uses first person—they'd be expected to identify the structure and explain how it functions or what effects it creates. By following Tantillo's lead in providing appropriate scaffolding while teaching real writing skills, and heeding Lemov's warnings about meaningless questioning, we can begin to serve our students as writers rather than simply as assignment completers.

References

Lemov, D. (2021). 'Phrasing Fundamentals' for Questioning: A TLAC 3.0 Excerpt. Teach Like a Champion.

Tantillo, S. (2016). Help Student Writers Find the Best Evidence. MiddleWeb.

Tantillo, S. (2016). Teach Students to Write Strong Paragraphs. MiddleWeb.