Talk as learning

Structured dialogue, rooted in both ancient wisdom and modern research, makes learning deeper and schools better

The landscape of education reform has long focused on curriculum design, assessment strategies, and pedagogical methods, yet often overlooked is perhaps the most fundamental element of learning: conversation itself. Dialogue—the exchange of ideas through structured talking and listening—represents not just a vehicle for transmitting knowledge but a transformative practice that shapes thinking, builds relationships, and creates meaning. As instructional leaders seek to improve educational outcomes, understanding the nature, structure, and potential of dialogue offers powerful insights for reimagining learning environments. The ancient Greeks recognized dialogue's centrality to knowledge construction; today's cognitive science confirms that quality conversation remains essential to deep learning and cognitive development.

Educational environments thrive or falter based on the quality of their conversational ecosystems. When students and teachers engage in rich, purposeful dialogue, learning deepens and educational goals become more attainable. When conversation is perfunctory or absent, even the most carefully designed curriculum fails to reach its potential. Dialogue represents more than casual exchange—it embodies a structured approach to collective meaning-making that has evolved from philosophical tradition into practical methodology. For educational reformers, understanding this evolution and its implications provides a pathway to transformative practice that transcends traditional educational paradigms.

Beyond its cognitive benefits, dialogue creates the relational foundation necessary for inclusive and equitable learning environments. Through conversation, diverse perspectives gain voice, silent knowledge becomes explicit, and communities of practice emerge. As we will explore, the intentional cultivation of dialogue creates spaces where both intellectual and socio-emotional growth can flourish. Educational leaders who center dialogue in their reform efforts tap into both ancient wisdom and cutting-edge understanding of how humans learn through interaction.

Last week’s blog in audio:

The historical foundations

The tradition of dialogue as a learning method traces back to antiquity, with competing claims about its origins. As Nikulin notes, "Zeno of Elea was the first to write dialogues, according to Diogenes Laertius; according to Aristotle, it was Alexamenus" (Nikulin, n.d., p. 1). However, it was Plato who transformed dialogue into both a literary genre and philosophical method, systematizing an approach to knowledge-building through questions and answers. This Socratic tradition established dialogue as more than conversation—it became "a way of life—of philosophical life—where the theoretical is intertwined with the practical in the activity of conversation" (Nikulin, n.d., p. 3). This understanding of dialogue as simultaneously intellectual and relational provides the historical foundation for contemporary approaches to dialogue in education.

The evolution of dialogue continued through Aristotle, who introduced important "innovations to dialogue, which lead it further away from spontaneous live conversation and closer to a rationalized literary—read and written—genre" (Nikulin, n.d., p. 4). This systematization established patterns of alternating between short exchanges and longer explanations that remain visible in educational discourse today. Through this historical development, dialogue emerged as a specialized form of communication with characteristics that distinguish it from casual conversation: intentional structure, dialectical movement between opposing viewpoints, and the centrality of questions that generate deeper inquiry. Educational reformers can draw from this rich tradition to understand dialogue's essential characteristics.

The classical conception of dialogue emphasizes that it is inherently "polyfocal or polycentric; it has at least two centers" (Nikulin, n.d., p. 5), requiring diverse participants with distinct perspectives to generate meaningful exchange. This historical understanding challenges contemporary educational models that privilege monologic instruction, suggesting instead that knowledge emerges through the interaction of multiple voices. Ancient dialogic practices also recognized that participants must be "true to life characters, real or imitative" who are "capable of questioning, answering, debating" (Nikulin, n.d., p. 5). This insight about authenticity in dialogue reinforces the importance of creating learning environments where genuine engagement—not just scripted interaction—can flourish.

The science of conversation

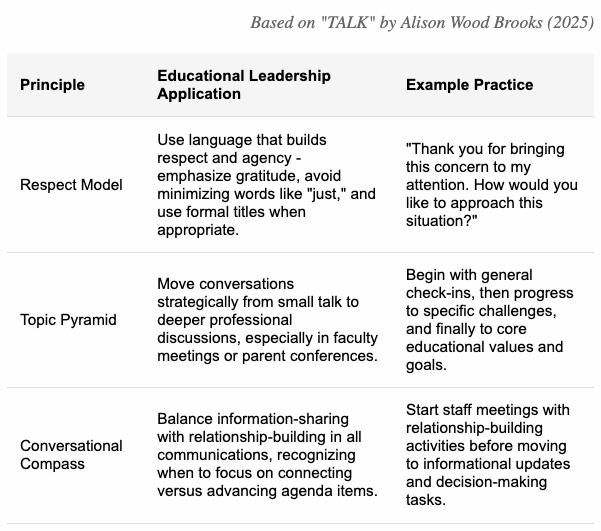

Contemporary research on conversation provides scientific validation for dialogue's educational power. Brooks (2025) offers a framework called the "conversational compass" that organizes conversational purposes into four quadrants: Protect, Savor, Advance, and Connect. This model helps instructional leaders understand that different conversational purposes serve different educational goals, from building safety and trust to advancing intellectual understanding. The framework suggests that effective dialogue in educational settings requires intentional movement between these purposes, creating conversational ecosystems that balance informational and relational elements. By mapping conversational intentions, educators can design dialogue experiences that serve specific learning objectives.

The structure of conversation also impacts learning outcomes, with patterns of questioning playing a critical role. Brooks (2025) documents how different question types emerge over time in conversation, showing that introductory questions give way to topic-switching questions, mirror questions, and follow-up questions as conversations progress. This progression mirrors the learning process itself, moving from initial exploration to deeper investigation. Educational dialogues that intentionally incorporate this natural pattern can more effectively support knowledge construction. Furthermore, conversation quality correlates with emotional states; Brooks (2025) provides an "emotions chart" mapping how conversational partners move through different emotional territories, suggesting that effective dialogue management requires attention to affective dimensions.

Brooks (2025) also introduces the concept of a "topic pyramid," illustrating how conversation naturally moves from surface-level small talk to deeper, more substantive exchange. For educational leaders, this model suggests that meaningful learning dialogue requires deliberate progression through increasing levels of depth and complexity. The transition from small talk to deep talk mirrors the pedagogical journey from basic comprehension to critical thinking and knowledge application. Research indicates that this progression doesn't happen automatically—it requires skilled facilitation and strategically designed conversational structures that support incremental movement toward more substantive exchange.

Practical applications for learning

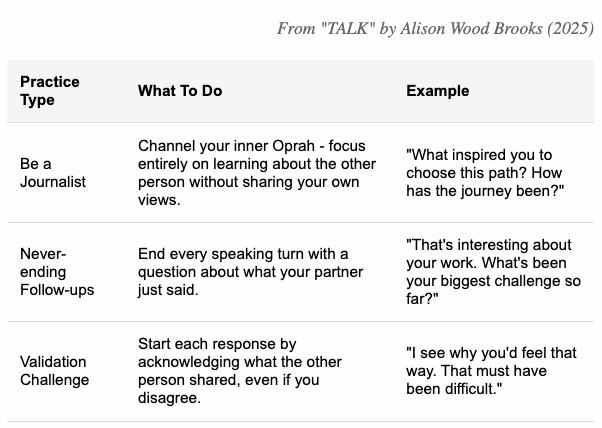

Implementing dialogue-centered approaches requires concrete strategies for structuring conversational learning. Brooks (2025) offers numerous practical exercises that can be adapted to educational contexts, including "Be a journalist," which trains students in deep listening and follow-up questioning techniques. Another powerful practice is the "validation challenge," where participants begin each statement by affirming what their partner just said—a technique that builds listening skills while creating psychological safety for further exploration. These structured dialogue activities can be integrated into existing curriculum to transform traditional lessons into more engaging, interactive learning experiences that develop both content knowledge and communication skills.

The quality of questions fundamentally shapes dialogue's educational value. Brooks (2025) provides extensive question sets, including "36 questions that lead to love" from Arthur Aron's research and 50 general conversation topics that can be modified for educational purposes. These question collections provide templates for creating inquiry-based discussions that progressively deepen engagement. Educational leaders can develop similar question sets tailored to specific content areas while preserving the psychological progression from lower-risk to higher-depth inquiries. Skilled educators can leverage these question patterns to guide learning conversations through predictable stages of development from initial exploration to substantive analysis.

Technology-mediated dialogue presents both challenges and opportunities for educational applications. Brooks (2025) suggests a "digital communication audit" that examines patterns of interaction across different modalities—an exercise that helps educational leaders understand how digital tools impact conversational quality. The rise of video conferencing, chat-based learning, and asynchronous discussion forums requires intentional adaptation of dialogue principles to these new contexts. Research indicates that digital dialogues often lack the natural rhythm and emotional attunement of face-to-face conversation, requiring more explicit structure and facilitation. Educational leaders must develop frameworks for effective dialogue that work across multiple modalities while preserving the essential qualities that make conversation educationally powerful.

Implications for educational leaders

For instructional leaders and education reformers, centering dialogue in educational practice requires systematic attention to both policy and pedagogy. At the policy level, leaders should examine how assessment systems, curriculum frameworks, and teacher evaluation criteria either support or inhibit quality dialogue. When educational outcomes are defined solely by standardized measures, the time and space needed for meaningful conversation often vanishes. Reform efforts should explicitly value dialogic competence as an educational outcome, measuring and rewarding the quality of classroom conversation alongside more traditional metrics. Additionally, professional development must equip educators with dialogue facilitation skills, moving beyond generic "discussion strategies" to deeper understanding of conversation architecture.

The physical and temporal organization of schools significantly impacts dialogue opportunities. Traditional classroom arrangements, rigid scheduling, and fragmented subject matter all create barriers to sustained, meaningful conversation. Educational leaders should reconsider fundamental structures: creating flexible learning spaces conducive to various conversation formats, building longer learning blocks that allow dialogue to develop naturally through Brooks' (2025) conversational stages, and designing integrated curriculum that supports sustained inquiry across disciplinary boundaries. Digital infrastructure decisions should similarly prioritize platforms that enable quality dialogue rather than just content delivery or assessment efficiency.

Perhaps most fundamentally, educational leaders must model dialogic approaches in their own practice. When faculty meetings, parent communications, and leadership team interactions exemplify quality conversation, the organization builds capacity for dialogue at all levels. As Brooks (2025) suggests in her reflection exercises, leaders should examine their own conversational habits, identify their goals and patterns, and intentionally develop their dialogue skills. By approaching educational reform itself as a dialogic process—where multiple perspectives are valued, questions drive inquiry, and understanding emerges through interaction—leaders create coherence between their methods and their message. In this way, dialogue becomes not just an instructional strategy but an organizational principle that transforms educational culture from the inside out.

References

Brooks, A. W.(2025). Talk. Random House USA.

Nikulin, D. V. (2006). On dialogue. Lexington books.