Student- or Teacher-Guided Discussion?

Is either more effective? Can we learn from both? What's the teacher's role?

As a preface to this, I must say that I'm not sure where I end up on this debate—though I do trend toward one position at this point. The question: What's the most effective role for the teacher during a discussion—is it as the "guide on the side" or "sage on the stage"?

As an high school English language arts fella, I've been around lots of discussion contexts in the classroom—and looked at them from both the teacher-planning perspective and the student-participation perspective. Most times when we're thinking about "discussion" it's typically envisioning a whole-group conversation which will, in some way, be evaluated by the educator. This means that individual participant contributions as well as their discussion-behavior will be assessed throughout the dialogue.

This is in contrast to some of the smaller opportunities for collaborative discussion in the context of teaching and learning: turn and talks, collaborative work, small groupings, etc. Many times a teacher will say, "We're having a discussion on Tuesday." And this typically means the class has been gearing up for a conversation, they've prepped some kind of claims and evidence around a question or set of questions, and the educator has shared—at least to some extent—how the participants will be evaluated within the discussion.

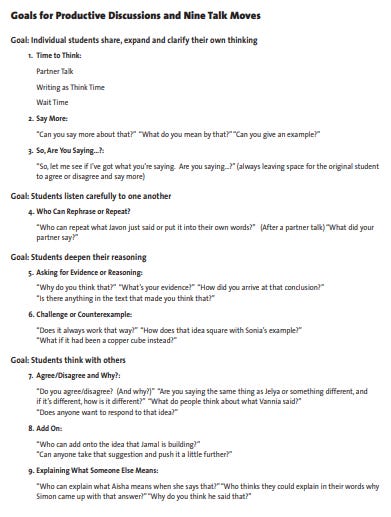

Maybe it's my totalizing zeal for "talk moves" or the interjection and interruption of "dialogic moves," but I've been wondering lately about the idea of leaving the kids to moderate their own discussion. I recognize the reading of the standards present there: from Kindergarten, the expectation of "asking and answering questions" is present in the Speaking and Listening standards, and by Grades 11-12 students are expected to "initiate and participate effectively in" as well as "propel conversations by posing and responding" to another in dialogue.

I recognize the vertical articulation of the standards, and the intentionality of building students' capacity to drive their own conversations by the high school level through thoughtful steps at each grade level. However, just like foundational reading skills, many high school students have not mastered speaking and listening standards present in the K-8 standards, and are not demonstrating the ability to meet these discussion standards in day-to-day classroom tasks, or more formalized “discussions.”

In fact, debates continue as to the more effective method for teaching (though it seems teacher-guided methods may be more justified in evidence at this time)—teacher-guided or student-activating. Too many times have I observed a classroom discussion and found students left to their own initiative performing an odd recital wherein they're taking turns sharing their claims and their evidence from a graphic organizer prepared prior to the discussion-event.

While the absence of teacher-guidance here (though only in the discussion-event itself; there's lots of evidence of teacher-guidance in the development of claims and selection of evidence) might flatter the standard language of "initiate" discussions, we're losing an exceptional opportunity to continue to guide the development of students' discussion acumen. Many times what a discussion needs to move from this inauthentic "recital" feel to an authentic, spontaneous "dialogic" feel is the thoughtful intervention or guidance of a teacher—one well-versed in the nature of discourse and conversation, and prepared to introduce talk moves to direct the conversation on different trajectories.

While I recognize opportunities to do this through student initiative—placing talk moves or conversation stems before students, asking them to select moves that drive conversation such as "Can you say more?", etc.—what are we losing by holding our tongues as educators while our students are expected to perform an authentic discussion? The time we're afforded with our scholars is so limited, and the expertise of our educators in so great, it seems a tremendous disservice to lock up models of mature discourse, demonstrations of exploratory talk, and exemplars of working with peers to promote civil, democratic discussions in service of a narrow evaluation of the students' "initiative."

I'd argue we're better positioned to recognize and evaluate students’ ability to propel conversations when we unlock them from an almost dialectic, recital type of turn-based sharing by voicing a few talk moves, pushing a few individuals to reveal their reasoning and thinking, and engendering a further climate of exploration, inquiry and investigation.