"Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I'll meet you there." Rumi's ancient wisdom captures a profound truth for modern educational leadership. In these verses, the 13th-century poet points to a space beyond binary opposition—a metaphorical field where seemingly contradictory ideas can coexist and enrich each other. This insight is particularly relevant for today's educational leaders, who constantly navigate complex challenges and competing demands.

In education, we often find ourselves trapped in dichotomous discourse: traditional vs. progressive teaching, teacher-centered vs. student-centered pedagogy, control vs. autonomy. Like Rumi's field beyond wrongdoing and rightdoing, research suggests that embracing paradoxical thinking—finding that space where opposites can coexist—offers a more nuanced and effective approach to educational leadership. When, as Rumi says, "the soul lies down in that grass, the world is too full to talk about." Perhaps similarly, when we move beyond simplistic either/or thinking, the rich complexity of educational practice becomes more apparent.

Understanding dichotomous discourse in education

Dichotomous discourse refers to the framing of concepts, ideas, or practices in mutually exclusive, binary terms. In education, this manifests as sharp divisions such as teacher-centered vs. student-centered instruction, where pedagogical approaches are viewed as either focusing on teacher authority and content delivery or prioritizing student autonomy and discovery learning. Similarly, we see this in debates about control vs. autonomy, where classroom management becomes an either/or proposition between enforcing rules and fostering self-regulation.

The traditional vs. progressive education divide represents another common dichotomy, positioning educational philosophies as either adhering to established practices or embracing innovation. This binary thinking simplifies complex issues, creating an "either/or" mentality that can polarize discussions and impede collaborative problem-solving. As Lefstein and colleagues (2017) observed in their study of Israeli teachers, dichotomous discourse can lead to adversarial relationships, hinder professional growth, and limit the exploration of effective teaching strategies.

The limitations of dichotomous thinking

While dichotomous discourse offers clarity and can simplify decision-making, it has significant drawbacks. Education is inherently complex, involving diverse student needs, cultural contexts, and educational goals. Binary oppositions fail to capture this complexity, leading to solutions that may be inappropriate or ineffective.

Dichotomous thinking often results in entrenched positions, where individuals or groups identify strongly with one side of an issue. This can create divisions among staff, reduce collaboration, and foster a culture of "us vs. them." By framing ideas as mutually exclusive, such discourse discourages the integration of different perspectives, limiting creative problem-solving and innovation.

Educational leaders frequently face paradoxes—situations where opposing demands are both essential. For instance, schools need to maintain high academic standards while supporting students' socio-emotional development. Dichotomous thinking forces a choice between the two, rather than finding ways to address both simultaneously.

Embracing paradox: A path forward

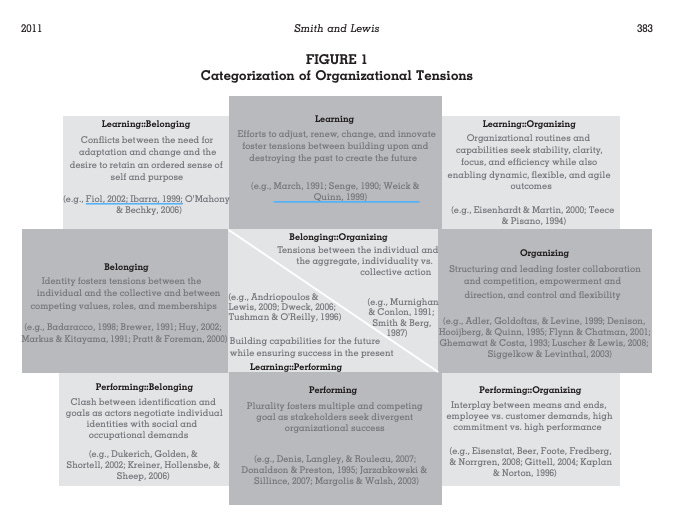

Adopting a paradoxical approach involves recognizing and accepting contradictory yet interrelated elements that exist simultaneously. Smith and Lewis (2011) define paradox as "contradictory yet interrelated elements that exist simultaneously and persist over time." This perspective allows educational leaders to navigate complexity without oversimplifying or disregarding important facets of the issues at hand.

Instead of choosing between opposing options, leaders can seek ways to incorporate both through "both/and" thinking. For example, combining teacher-directed instruction with student-led exploration can address diverse learning needs. By identifying the strengths of different approaches, leaders can develop integrated strategies.

The "dynamic equilibrium model" proposed by Smith and Lewis suggests organizations continuously adjust to balance competing demands. In education, this might involve regularly reassessing and adjusting practices to align with both accountability requirements and the promotion of creative, critical thinking. Creating safe spaces for teachers and leaders to share diverse perspectives without judgment becomes crucial for fostering open dialogue that acknowledges and explores contradictions.

Practical implications for educational leaders

Educational leaders can take several concrete steps to move beyond dichotomous thinking. First, they should cultivate paradoxical thinking by modeling and promoting openness to contradictory viewpoints. Professional development that highlights the value of paradox and trains staff in both/and thinking can enhance this capacity.

Leaders should redesign collaborative structures to focus on exploring dilemmas rather than seeking quick resolutions. By leveraging diverse perspectives and embracing different pedagogical philosophies, they can create more robust and flexible strategies that meet varied student needs.

Ongoing reflection on personal beliefs and biases that may contribute to dichotomous thinking is essential. Finally, policy-making should avoid one-size-fits-all solutions in favor of flexible approaches that acknowledge educational complexities and paradoxes.

Breaking free from dichotomous discourse is essential for educational leaders striving to navigate modern education's complexities. By embracing paradoxical thinking, leaders can move beyond limiting binaries, foster collaborative environments, and develop innovative solutions that address multiple needs simultaneously. As research underscores, acknowledging and working with paradoxes can lead to enhanced learning, creativity, and organizational sustainability.

References

Lefstein, A., Trachtenberg-Maslaton, R., & Pollak, I. (2017). Breaking out of the grips of dichotomous discourse in teacher post-observation debrief conversations. *Teaching and Teacher Education*, 67, 418–428.

Schad, J., Lewis, M. W., Raisch, S., & Smith, W. K. (2017). Paradox research in management science: Looking back to move forward. *Academy of Management Annals*, 11(1), 5–64.

Smith, W. K., & Lewis, M. W. (2011). Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. *Academy of Management Review*, 36(2), 381–403.

I think it is a given that good school leadership embraces paradoxical thinking and so action. That applies to the adults in a school and can, within the right circumstances, apply to students too. There are very few decisions we make in school that don't have either recognized or unintended consequences beyond the planned positive outcomes. how could it be otherwise in a complex system?

What's interesting to me is always the boundary discussion. In practical terms this is where I think the most tricky elements of leadership, including team efficacy and collective efficacy, reside. Take for example the question of belonging. In any community there is both a zone of belonging and a space outside that zone. In some circumstances, for example where there is a very clearly defined mission and/or set of values the community ascribes too and the leadership maintains, those discussions are very concrete. However, in most schools that boundary is both soft and sometimes even very faintly defined. That might be due to the desire to leave open possibility, or it might be due to a lack of clarity over collective norms, which explicit or implicit. It is these spaces that dilemma based thinking and so paradoxes are very real. Good leaders understand this I believe and are comfortable being to some extent uncomfortable in these spaces.