Learning and teaching through problems

I returned to teaching and learned that folk wisdom, not reform ideals, helps navigate the persistent problems that define classroom life.

The fall semester was really tough. Returning to high school teaching after time away, I found myself overwhelmed by what seemed like basic challenges—student behavior, lesson momentum, the sheer chaos of twenty-seven teenagers in one room. My wife offered me a gardener’s wisdom: “First year you sleep, then you creep, then you leap.” This folk saying became my lifeline. Now, at the start of the spring semester with lessons flowing and students engaged, I’m reflecting on how this return journey connects to Mary Kennedy’s insights about why teaching resists reform and to deeper paradoxes about transformation itself.

What strikes me now is how much of my teaching knowledge comes not from graduate courses or professional development but from what I call folk epistemology—wisdom passed through conversation, metaphor, and lived experience. I return again and again to the Rumi saying: “Once I was clever, so I wanted to change the world. Now I am wise, so I am changing myself.” This is reform wisdom of a different kind—not the ambitious program rolled out district-wide, but the quiet recognition that sustainable change begins with accepting what is.

Kennedy’s research helps me understand why my fall struggles were inevitable and why my strong spring start feels so hard-won. She reveals how classroom teaching operates within constraints that reformers rarely acknowledge—the constant interruptions, the need to orchestrate time and materials and ideas and twenty-seven different minds simultaneously, the reality that intellectual engagement itself can disrupt rather than enhance learning. Reading her work this semester, I see my own experience reflected: the gap between what I wanted to accomplish and what the daily realities of classroom life actually permitted.

When everything falls apart

My fall semester looked like failure from the outside. Lessons fell flat. Student behavior problems erupted daily. I couldn’t seem to manage the basic flow of a class period, much less create the intellectually rigorous, deeply engaging learning experiences I envisioned. I felt like I had forgotten how to teach, like all my years of experience had evaporated. What I thought would be a triumphant return felt more like being buried alive.

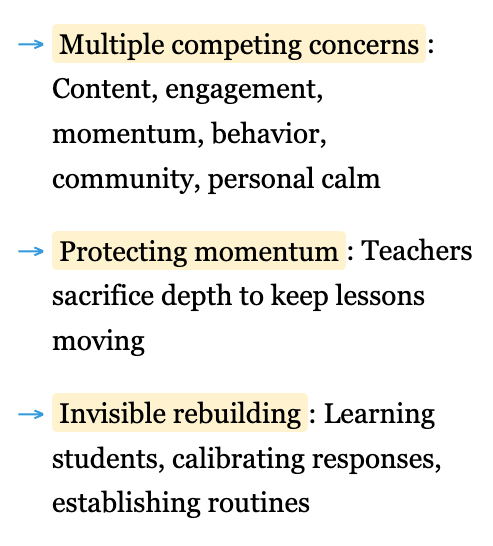

Kennedy’s analysis of classroom life helps me see this differently. She shows how teaching demands attention to far more than reformers typically acknowledge: not just content and engagement but also lesson momentum, classroom community, behavioral norms, and teachers’ own needs for order and calm. When these concerns conflict—as they constantly do—teachers instinctively protect momentum, sometimes at the cost of deeper learning. My fall semester was spent relearning this juggling act, rebuilding the tacit knowledge of how to keep all these balls in the air simultaneously.

What looked like chaos was actually the invisible work of rebuilding. I was reestablishing routines, learning these particular students, calibrating my responses to their specific needs and patterns. Kennedy notes that teachers construct practices largely in isolation, dependent on students for evidence of success or failure. My fall was this painful recalibration—learning through daily failure what would and wouldn’t work with these students in this building at this moment. The struggle wasn’t wasted; it was the necessary foundation for what would come.

Small movements forward

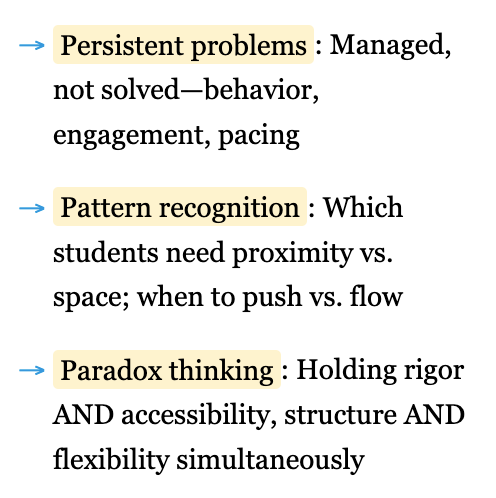

As winter approached, things began to shift almost imperceptibly. Not dramatic breakthroughs but small improvements—a smoother transition between activities, a classroom discussion that didn’t derail, a behavior intervention that actually worked. Kennedy describes teaching as managing “persistent problems” rather than solving them once and for all, and this resonated deeply. Student behavior didn’t disappear as a challenge; I just got slightly better at managing it. Content didn’t suddenly become inherently engaging; I got better at portraying it in ways that captured attention.

This growth emerged from what I think of as folk epistemology—practical wisdom gained through experience rather than formal training. I started to notice patterns: which students needed proximity, which needed space; when to push for depth and when to prioritize momentum; how to respond to unexpected student ideas without losing the thread of the lesson. These insights didn’t come from professional development or curriculum guides but from daily practice and reflection, from trial and error, from conversations with colleagues in the hallway.

The paradox papers I’ve been reading help me understand this phase differently. Just as Chittick describes spiritual seekers accepting both divine mercy and severity, I was learning to accept both my teaching successes and failures as part of a larger pattern. Just as Smith and Lewis show that organizational sustainability requires continuously balancing competing demands rather than resolving them, I was learning to hold multiple teaching tensions simultaneously—rigor and accessibility, structure and flexibility, content coverage and deep engagement. Progress wasn’t linear but rhythmic, getting slightly better at the dance.

When problems become manageable

Spring semester has started well. Not perfectly—teaching is never perfect—but with a quality I can only describe as flow. Kennedy identifies how teachers must simultaneously orchestrate time, materials, students, and ideas, and somehow this orchestration is more fluid. I can anticipate where students will struggle, better design activities that engage without overwhelming, better respond to unexpected questions without losing the lesson’s direction. The persistent problems haven’t disappeared, but they have become manageable in ways that free attention for what matters most: helping students encounter important ideas.

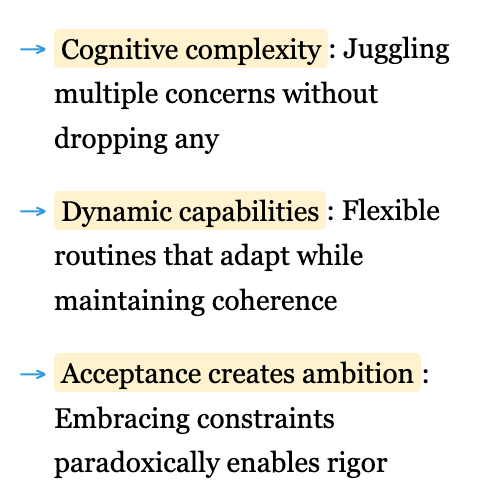

What changed? Kennedy’s analysis suggests that effective teaching requires cognitive and behavioral complexity—the ability to hold multiple competing concerns simultaneously and respond flexibly in the moment. My fall semester rebuilt this capacity through repetition and failure. My winter work refined it through small adjustments. By the spring semester, I have regained what Kennedy calls “dynamic capabilities”—routines flexible enough to adapt to changing circumstances while maintaining coherence and direction. I could attend to student behavior without sacrificing intellectual depth, could pursue unexpected student questions without losing sight of learning goals.

This transformation has taught me something crucial about the folk wisdom that guides my teaching. The Rumi quote I return to—”now I am wise, so I am changing myself”—captures what Kennedy demonstrates throughout her research: reform fails when it ignores the realities teachers face and the complex reasoning they employ. My strong spring start comes not from implementing someone else’s reform agenda but from accepting my own limitations, my students’ actual needs, and the genuine constraints of classroom life. Paradoxically, this acceptance created space for ambition—for rigorous content, intellectual engagement, and genuine learning.

Implications for practice

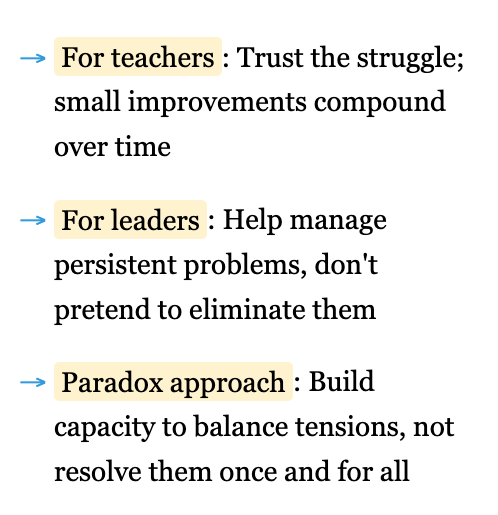

For teachers facing their own difficult seasons—whether returning after time away or simply struggling through a hard year—Kennedy’s research offers crucial permission. She shows that teaching is inherently difficult, that the gap between reform ideals and daily practice stems not from teacher inadequacy but from the genuine complexity of the work. Allow yourself the struggle: the fumbling, the failures, the painful construction of classroom knowledge. Trust the small improvements, the incremental growth, the slow accumulation of practical wisdom. Transformation will come, but only if you don’t abandon yourself during the hard times.

For instructional leaders and reformers, Kennedy’s work demands humility about what can be changed and how. She shows that teachers already hold values aligned with reform ideals—they want rigorous content, intellectual engagement, and universal access to knowledge. But they also face persistent problems that reform proposals rarely acknowledge: the interruptions, the behavioral challenges, the logistical complexities of managing learning in large groups. Effective support means helping teachers manage these persistent problems rather than pretending they don’t exist or can be eliminated through better curriculum or more professional development.

The paradox literature suggests a different approach entirely: recognizing that excellent teaching requires continuously balancing competing demands rather than resolving tensions once and for all. Leaders might stop asking teachers to choose between rigor and accessibility, between structure and flexibility, between content coverage and deep engagement—and instead help them develop the cognitive and emotional capabilities to hold these tensions simultaneously. This means protecting time for teachers to reflect and plan, creating structures for collegial exchange of practical wisdom, and reducing the organizational interruptions and constraints that make teaching harder than it needs to be. The wisdom isn’t in the reform program but in supporting teachers’ capacity to navigate classroom complexity with grace.

References

Chittick, W. C. (2013). The religion of love revisited. Journal of the Muhyiddin Ibn Arabi Society, 54, 37-59.

Kennedy, M. M. (2005). Inside teaching: How classroom life undermines reform. Harvard University Press.

Smith, W. K., & Lewis, M. W. (2011). Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 381-403.

Really insightful take on the gap between reform ideals and classroom reality. Kennedy's framework around persistent problems versus solvable ones reframed how I think about my own teaching struggles last year. That first year sleep-creep-leap metaphor hits different when applied to pedagogy rather than perrenials. The piece makes a strong case that real growth comes from accepting complexity rather than trying to eliminate it throught standardized solutions.

I love the paradox. Holding two things simultaneously: rigor and access, structure and flexibility. What a gift for students and educators alike.