Icebreakers don't suck

Research shows well-designed conversational icebreakers boost adult learning by creating psychological safety and meaningful engagement

The mere mention of "icebreakers" often elicits groans from both educators and learners across all age groups. Many view these activities as frivolous time-wasters—awkward exercises that delay getting to the "real work" of learning. Yet this dismissive attitude overlooks substantial evidence that well-designed icebreakers can serve as powerful instructional tools that enhance engagement, build community, and improve learning outcomes for participants of all ages.

The research shows that far from being superficial add-ons, thoughtfully implemented icebreakers can be integral components of evidence-based teaching practice across educational contexts, including professional development, higher education, and community learning settings. Sasan, Tugbong, and Alistre (2023) demonstrated quantitatively that icebreakers significantly increase engagement and participation, while Carmeli, Brueller, and Dutton (2009) identified the crucial relationship between interpersonal connections, psychological safety, and learning behaviors. These findings align with Brooks' (2025) conversational framework, which helps us understand how skillful conversation management builds trust and facilitates learning.

When we dismiss icebreakers as mere "fluff," we miss an opportunity to leverage powerful relational dynamics that drive learning. Adult learners especially benefit from participation in relevant experiences and practical information (Karge et al., 2011). Thoughtfully designed icebreakers create precisely these kinds of experiences while simultaneously building the psychological foundations necessary for productive learning environments. By understanding the science behind effective icebreakers, we can transform them from dreaded activities to essential pedagogical tools that respect the intelligence and experiences of adult learners.

Building psychological safety

Research consistently demonstrates that psychological safety—the shared belief that a learning environment is safe for interpersonal risk-taking—is foundational to effective learning, particularly for adults. In their influential study, Carmeli, Brueller, and Dutton (2009) found that high-quality interpersonal relationships significantly enhance psychological safety, which in turn promotes learning behaviors. Their research revealed that both the capacity of high-quality relationships and the subjective experiences of these relationships were positively associated with psychological safety and, ultimately, learning behaviors.

When adult learners feel psychologically safe, they are more willing to engage in behaviors essential for learning, such as seeking help, asking for feedback, speaking up about mistakes, and testing work assumptions (Carmeli et al., 2009). Icebreakers create opportunities for building these high-quality relationships that foster psychological safety. By reducing interpersonal barriers and creating shared positive experiences, these activities establish the relational foundation necessary for risk-taking and authentic engagement with challenging material—what Brooks (2025) identifies as moving from "protect" to "advance" and "connect" quadrants in her conversational compass.

This psychological safety is particularly important for adult learners, who often bring significant prior knowledge and experience—as well as potential anxieties and vulnerabilities—to the learning environment. Karge et al. (2011) emphasize that adult learners need to be respected and valued, and well-designed icebreakers can signal this respect by acknowledging and leveraging their expertise and life experiences. Rather than infantilizing adult learners with silly games, effective icebreakers create opportunities for meaningful connection that honor their maturity and complexity.

Icebreakers as conversational moves

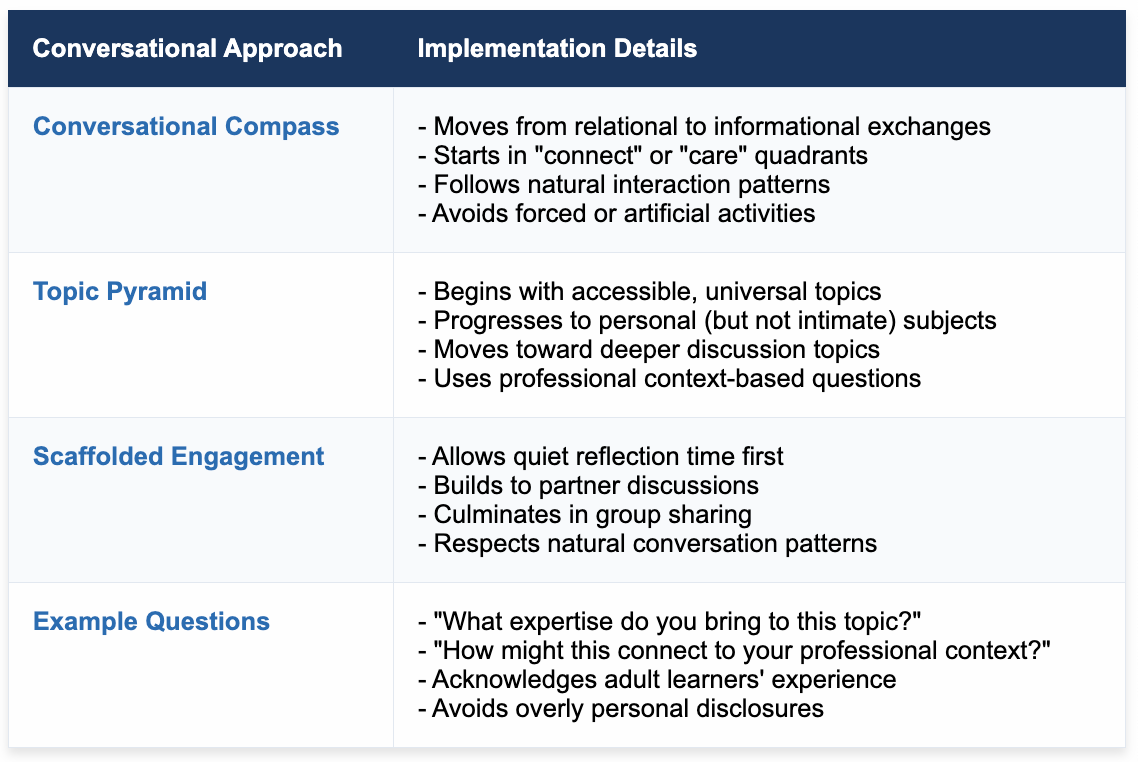

One of the most important insights from Brooks' (2025) work is that effective icebreakers need not be elaborate games or awkward team-building exercises. Instead, they can be simple conversational moves that we naturally use in everyday interactions. Brooks identifies a "conversational compass" that maps different kinds of exchanges along two dimensions: informational and relational. Effective icebreakers often start in the high-relational quadrants ("connect" or "care") before moving toward more informational exchanges. These conversational pathways reflect natural human interaction patterns rather than artificial "forced fun"—an approach that particularly resonates with adult learners who may resist activities that feel patronizing.

Brooks' (2025) "topic pyramid" framework further illustrates how simple conversational moves function as effective icebreakers. The pyramid starts with easy topics anyone could discuss at the bottom and moves upward through personal but not intimate topics to deeper subjects at the top. Skilled facilitators of adult learning naturally move up and down this pyramid, building trust and engagement through thoughtful question-asking and response patterns. Simple starters like "What expertise do you bring to this topic?" or "How might this connect to your professional context?" function as natural icebreakers that acknowledge the valuable experiences adult learners bring to the table without demanding uncomfortable personal disclosures.

Karge et al. (2011) highlight the effectiveness of structured professional dialogues as sophisticated icebreakers. This approach begins with brief individual reflection on a field-relevant prompt, followed by focused small-group discussions where professionals can share insights from their experiences. For instance, asking participants to consider "What's the most significant change you've observed in our field over the past five years?" or "What's a common misconception about our profession that you frequently encounter?" creates natural entry points for meaningful dialogue. This method honors adult learners' professional identity and expertise while fostering authentic connections through shared professional experiences and challenges. Unlike traditional icebreakers, these conversations emerge organically from participants' real-world knowledge and concerns, creating engagement through relevant, purposeful exchange rather than artificial social activities.

The empirical case for icebreakers

The empirical evidence for icebreakers' effectiveness is compelling across different learning contexts and age groups. Sasan, Tugbong, and Alistre (2023) conducted a mixed-methods study that demonstrated significant improvements in engagement after implementing icebreaker activities. Their data showed that participants in the icebreaker group reported feeling a greater sense of community and connectedness with their peers and experienced an improved learning atmosphere and mood. This improved learning climate directly translated to increased willingness to participate in learning activities.

These findings align with Brooks' (2025) observations about how psychological safety enables more productive conversations. When people feel safe, they are more willing to engage in learning behaviors such as seeking feedback from others and speaking up about mistakes and testing work assumptions (Carmeli et al., 2009). These small conversational moves create the conditions for more meaningful and productive learning exchanges.

These benefits are particularly pronounced for adult learners. Karge et al. (2011) note that adults learn best through participation in relevant experiences and practical information, and that when adult learners are active in their learning, they develop critical thinking skills, receive social support systems for learning, and gain knowledge efficiently. This understanding of adult learning principles further supports the strategic use of icebreakers in educational settings with adult learners. Structured interactive activities provide exactly the kind of active, participatory learning experiences that adult learners need to thrive, while respecting their intelligence and autonomy.

Implications for practice

For educational reformers and instructional leaders working with adult learners, these findings suggest several practical implications. First, we should reframe icebreakers not as optional add-ons but as essential conversational tools that create the relational and psychological foundations for effective learning. Brooks' (2025) framework reminds us that simple, everyday conversational moves—thoughtful questions, attentive listening, appropriate self-disclosure—can function as effective icebreakers without the need for elaborate games or activities. Educational leaders should help instructors develop these conversational skills rather than providing them with a catalog of awkward team-building exercises that may alienate adult learners.

Second, icebreakers should be brief, frequent, and integrated throughout the learning experience, not just used at the beginning of a course. Sasan et al. (2023) conducted their study over the course of one semester, suggesting that the benefits of icebreakers accumulate over time. Brief conversational moves—a quick check-in at the beginning of a session, a mid-session pair discussion, or a reflective closing question—can serve as "micro-icebreakers" that maintain engagement and strengthen relationships throughout a learning experience. This approach is particularly valuable for adult learners, who may have limited time for learning and want to feel that every moment is purposeful and productive.

Finally, we should approach icebreakers with intentionality and adaptability, especially when working with adult learners who bring diverse experiences and expectations to the learning environment. Brooks' (2025) framework helps us understand that different conversational purposes require different approaches. A professional development session that needs to build community might benefit from more connect-oriented exchanges, while a group struggling with difficult content might need more care-oriented conversations. By approaching icebreakers as natural, flexible conversational moves that honor adult learners' intelligence and experience rather than rigid protocols, instructional leaders can help transform them from dreaded exercises to powerful tools for educational transformation.

References

Brooks, A. W. (2025). Talk. Random House USA.

Carmeli, A., Brueller, D., & Dutton, J. E. (2009). Learning behaviours in the workplace: The role of high‐quality interpersonal relationships and psychological safety. Systems Research and Behavioral Science: The Official Journal of the International Federation for Systems Research, 26(1), 81-98.

Karge, B. D., Phillips, K. M., Jessee, T., & McCabe, M. (2011). Effective strategies for engaging adult learners. Journal of College Teaching & Learning (Online), 8(12), 53.

Sasan, J. M. V., Tugbong, G. M., & Alistre, K. L. C. (2023). An exploration of icebreakers and their impact on student engagement in the classroom. Science and Education, 4(11), 195-206.